“Air lease” technology had its origins in the area near

Air lease technology was advantageous for intermittent pumping operations such as at Windy City because the compressor engines could be rapidly started and placed into operation, matching engine operation to the needs of oil pumping.

Ronald Moyer of

The first tragedy occurred February 2, 1926, when Ronald's uncle, Merle Monroe Moyer, was killed while servicing a well in the field. The descent of a string of two-inch tubing could not be controlled by the engine and it oversped. This overspeed condition caused the balance ring on the flywheel to explode, sending pieces of the ring flying at high speed. According to an article in The Kane Republican for February 3, 1926, and their retrospective article on February 2, 1956, Merle received critical injuries, including a skull fracture. At age 29, he died at his home in Russell City, Pensylvania, shortly after the accident.

A second tragedy occurred December 26, 1940, when Lee Moyer, working with his brother Clifton, was also killed by an exploding balance ring. Again, the engine could not be slowed by air pressure when applying the reverse lever. A piece of the ring struck Lee in the abdomen, severely injuring him. The Kane Republican for December 27, 1940, reports that Clifton moved Lee from the well site to Lee's home nearby. He was then transported by ambulance to Kane Summit Hospital, where he passed away the next morning at age 37.

At that time,

This photo shows the

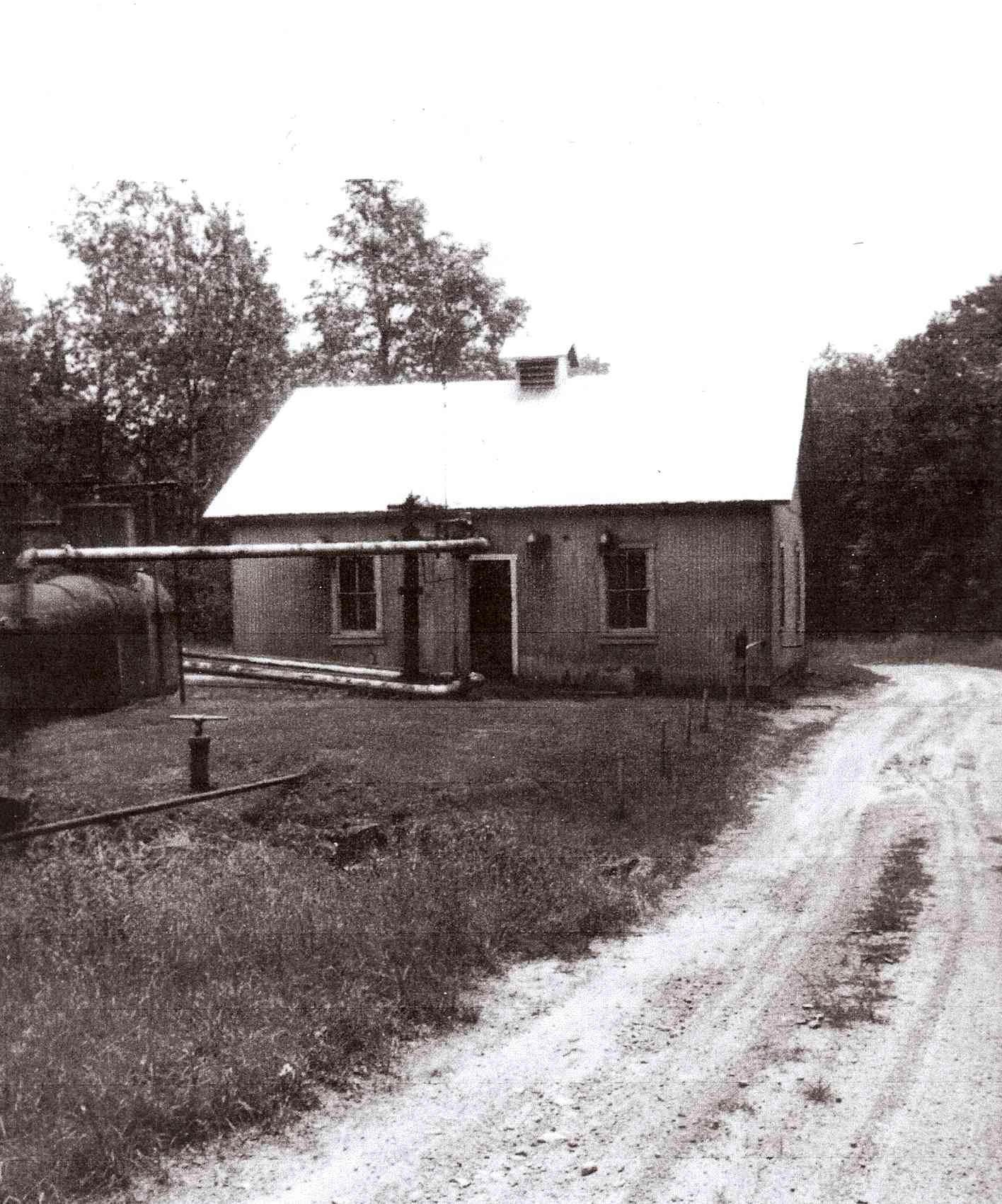

This photo shows the front of the building in the 1980s. The wide doors beneath the porch roof provided access to the machinery inside.

This view of the rear of the building, also in the 1980s, shows the air piping leaving the building. The “shell side” of one of the original steam boilers, to the left in the photo, was used as an air receiver. Note the T-handle valve in the center of the photo. It operated a bypass that could dump compressed air to the area of the engine exhaust pit, which is ahead of and to the right of the valve.