August 2025

A Tribute to Paul Earle Harvey, M.D.

July 6, 1944 – February 19, 2025

By W. Norm Shade

On

June 20, the Coolspring Power Museum’s Board of Directors arranged a

special presentation to honor Dr. Paul Harvey and reflect on his life.

I had the honor of presenting that tribute, held at the Coolspring

Presbyterian Church, which Paul belonged to throughout his life.

This issue of The Flywheel presents Paul’s tribute in written

form. It includes numerous excerpts from an excellent article

written by Sara Welch for the March 11 issue of FARM and DAIRY.

On

June 20, the Coolspring Power Museum’s Board of Directors arranged a

special presentation to honor Dr. Paul Harvey and reflect on his life.

I had the honor of presenting that tribute, held at the Coolspring

Presbyterian Church, which Paul belonged to throughout his life.

This issue of The Flywheel presents Paul’s tribute in written

form. It includes numerous excerpts from an excellent article

written by Sara Welch for the March 11 issue of FARM and DAIRY.

Dr. Paul Harvey was a co-founder of the Coolspring Power Museum, and, here, his collection provided the foundation for the largest collection of historically significant stationary internal combustion engines in the United States. But Paul Harvey lived a full life, wearing many hats in his 80 years in Coolspring, where he spent most of his life in the house he grew up in.

He was a boy practicing his trumpet on the front porch — much to his neighbor’s dismay. He was a college kid selling Compton’s Encyclopedias door-to-door. He was an avid collector of early gas engines in Western Pennsylvania. He was a doctor at DuBois and Brookville hospitals and Allegheny Health Center for 50 years — and a doctor who would accept same-day house calls from the residents of Coolspring. He was the owner of the Coolspring General Store because he wanted to preserve it for as long as possible. He was a co-founder and permanent board member of the Coolspring Power Museum. He was a member of the Coolspring Presbyterian Church, where he was an elder and a Sunday school teacher. He was a son, husband, father, grandfather and friend.

Paul was easily recognized around Coolspring, driving his John Deere Gator and smoking his pipe. So naturally, following his death on Feb. 19 of this year, he was buried with his pipe and a pouch of tobacco tucked into the pocket of his red plaid flannel shirt. He was also well-known among antique engine collectors all over North America. He was always searching for his next great find — a passion that started when he was a sophomore in high school and led to the inception of the Coolspring Power Museum (“CPM”).

Back

in the fall of 2019, before COVID hit us hard, I spent many hours

researching the history of CPM, which was published as the 2021

Bores & Strokes. A copy of the booklet’s cover is shown in Figure

1. The booklet, THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH, can be

purchased online or at the CPM Gift Shop.

Back

in the fall of 2019, before COVID hit us hard, I spent many hours

researching the history of CPM, which was published as the 2021

Bores & Strokes. A copy of the booklet’s cover is shown in Figure

1. The booklet, THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH, can be

purchased online or at the CPM Gift Shop.

My research included a number of long chats with Paul. And at my request, in early 2020, he wrote down many recollections that we published. I’m going to use some of that to let Paul tell his story in his own words.

Paul wrote: “I have been one of the very fortunate persons to have lived in the same home in Coolspring my entire 76 years. I have seen communication progress from wall mounted crank telephones to the iPhone as well as the evolution of many other modern miracles. I was privileged to have attended six years in a one room school where all the boys carried pocket knives.”

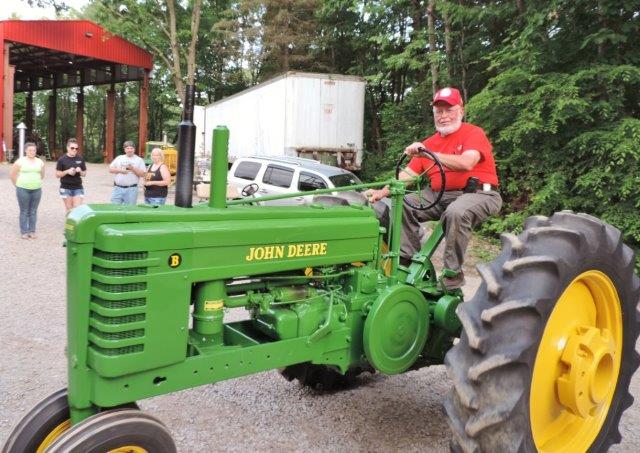

“I helped my Dad farm our fields with his John Deere H (Figure 2), which is still here and working. So, country life has treated me very well, and my profession has allowed me to live here and enjoy it as I watch the world pass by.”

“My maternal grandfather, P. P. Horner, M.D., was a country doctor and his office building is still here (Figure 3). Sadly, he passed before I was born."

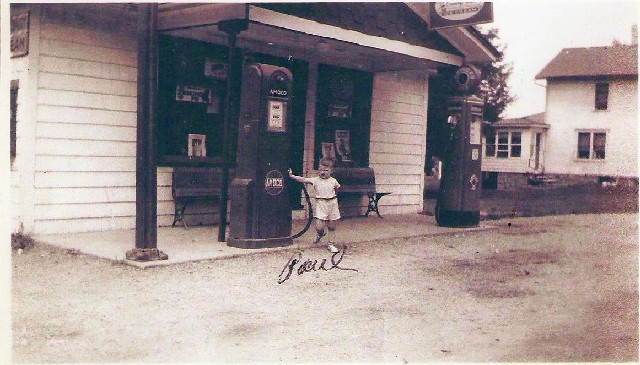

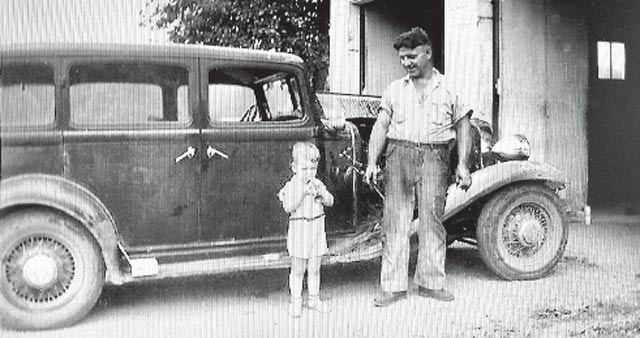

My mother, Arlene, a school teacher, certainly influenced my profession, but my father, Earle, a mechanic, fostered my love of anything mechanical. He returned home at the end of WW2, where he had worked at Firestone Tire in Akron, Ohio. He opened his little business here and sold Amoco gasoline, as well as food items and auto parts in a little store (Figure 4). The building also had his auto repair shop. Somehow, he found time to farm the fields, raise some pigs and a steer or two, and tend his chickens. I helped with all. His garage is now the building at the museum’s entrance that is used as our repair shop. I watched him work on all kinds of vehicles as well as tractors and lawn mowers. And so my interest grew. He patiently taught me all my mechanical skills such as welding and brazing, mechanics and lathe operation. It was a wonderful life in those early days to look forward to lunch on the old kitchen table with Arley and Earle.”

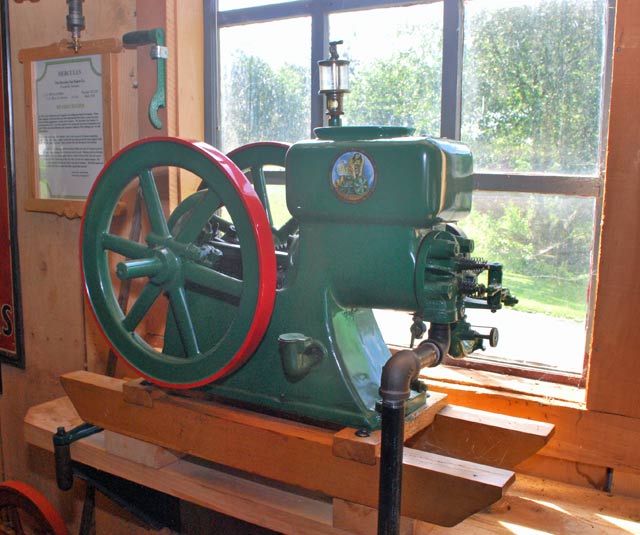

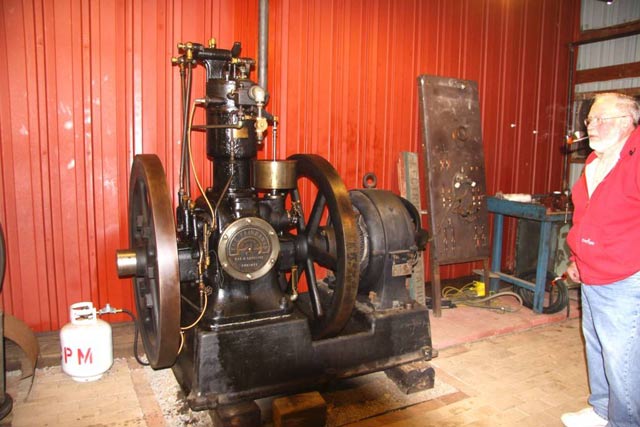

“Back in 1958, I was a sophomore in Punxsutawney High School. That autumn, I would frequently take my beagle, Tootsie, and the old 12 gauge, and go for a bunny or two. Of course, I had to feed the chickens and gather the eggs first. One evening I headed across some fields east of town where a gas well was being drilled with a massive standard rig. Tootsie and I gave it wide berth but then heard an odd sound. Following it, we found a strange engine belted to a water pump supplying the rig. Wow, never imagined anything like this! Actually, it was an International LA. Next evening I went back and chatted with the driller, a kindly gent who taught me all about the rig and drilling. Finally, after many visits, I asked him if he had a similar engine for sale. He confirmed, so I asked my Dad if I could spend $5.00. I made a quick trip back to pay him and he promised to drop it off when he returned. Next evening, a wonderful 1½ horsepower Hercules was waiting for me. My Dad and I had a wonderful winter taking it apart, cleaning parts and making gaskets, and finally getting it running. Now it is proudly displayed in the window of the Machine Works (Figure 5) and happily runs for all our shows.”

“Over the next couple of years, I found a few engines

locally including a Waterloo, Detroit, Witte, a couple of Briggs and

Strattons, and a Maytag. All were fun to get running and my Dad was as

enthused as I! With no internet, we learned by trial and error.”

“But then college came, first Clarion State College in Clarion, Pennsylvania.; then St Vincent College in Latrobe, Pennsylvania., to prepare for medical school. Unfortunately, the engines had to be set aside for several years. College and the first two years of medical school at West Virginia University in Morgantown were hard didactic classroom work and I had no time for anything else. Finally in 1967, as I was about to start my last two clinical years, I had some free time. My parents and I decided to take a relaxing vacation to the Lancaster, Pennsylvania area. Amid all the Amish sites, I happened upon a most unique museum named Rough and Tumble Engineers. After I spent several hours touring the grounds in utter amazement of the mechanical wonders, the older gent at the gift shop suggested that I contact another young engine enthusiast named John Wilcox. I was determined to do so, and a life-long friendship developed!”

“Soon after returning to school in Morgantown, I wrote a letter to John That was the usual method of communication at that time! A reply soon came, and he invited me to travel with him to the upcoming August show at Rough & Tumble. He picked me up at my apartment, and what a fantastic world of gas engines evolved. He explained the various gas engines and taught me the starting procedures. Thoroughly delighted, I was entrusted to operate a few during the show. I was hooked for life.”

“At John’s advice, I discovered the oil field just west of Morgantown, which was filled with wells powered by gas engines. That fall, instead of attending football games, I searched for unique engines. Now with some free time during my clinical years, I found a myriad of oil wells, all powered by gas engines, just west of Morgantown. Most were Bessemers, Reids, and South Penn Specials. Returning as often as possible, I met a very friendly well pumper, Les Neely, who occasionally invited me to accompany him in his old International Scout on his pumping rounds. Les taught me how to start and care for the engines and pump the wells. Imagine eating lunch beside one well and listening to the sound of three others, recognizing when one pumped off. Some summer evenings after a hard day at school, I would drive out to my favorite well, start the engine, and just sit and watch. So peaceful!”

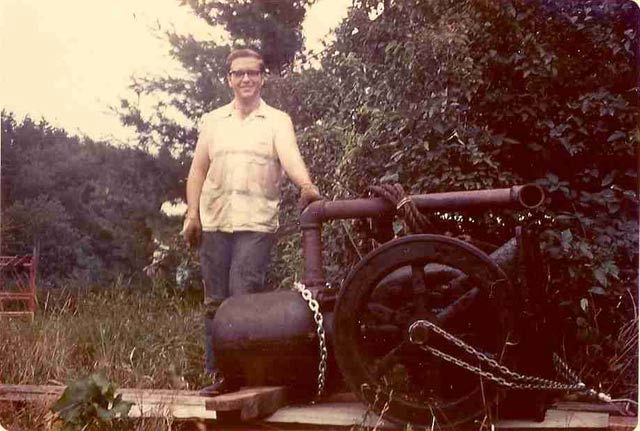

“Subsequently, John Wilcox and I spent many weekends touring the oil fields of West Virginia, Ohio, and southwestern Pennsylvania, always in search of the unique engine. I was introduced to the Eureka Pipeline Company, and saw my first Klein at their Dolls Run Station in Core, West Virginia. To conclude a wonderful summer, I visited John’s autumn Flywheel Roll at his old Buckeye Pipeline’s station, Trail Run, for two days. Wow! So many unusual engines! I was definitely hooked. I truly think that visit cemented a life-long friendship (Figure 6).”

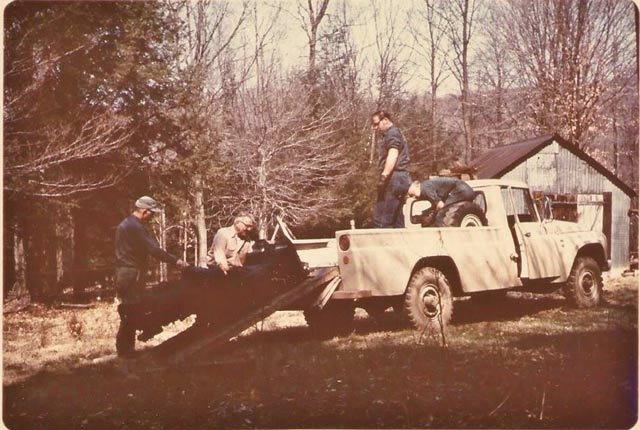

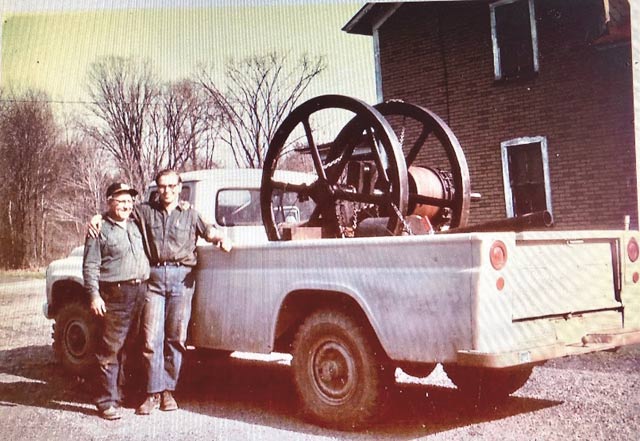

Figure 6: Paul & John with Model 4 Klein on John's Truck.

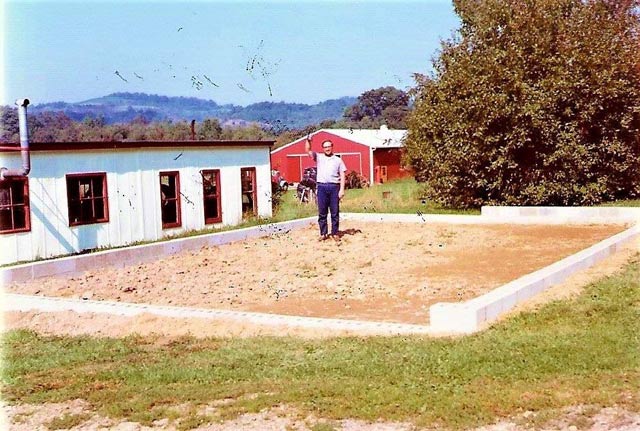

“Next summer while I was on break, my Dad and I decided to build the Engine House. This 12’ by 20’ structure would be everything that a collector could ever want. I already had a 6 horsepower IHC Famous, found on a West Virginia farm, and was buying a 9 by 12 Model 4 Klein from John. Soon the building was completed and included also an Araco and a vertical Kline. As I completed the electrical and gas service, I was quite content that I had the most wonderful place to play. After two additions, it has become the present Founders Engine House (Figure 7). Little did I know what had been started!”

Figure 7: Founder's Engine House, 2020.

“Upon graduating from medical school in 1969, I did my internship at Washington Hospital in Washington, Pennsylvania. It was an excellent community hospital that prepared me well, but I must admit that the proximity to a yet unexplored oil field influenced my choice.”

“A lot happened that year! I had been using my faithful 1965 IHC pickup for all my engine moves (Figure 8). But now I was finding bigger engines that begged to be saved. Exploring around Franklin, Pennsylvania, I found a 1946 Reo winch truck that belonged to Fowler and Fowler, Reo and sawmill equipment dealers in Oil City, Pennsylvania. It was on Ed Fowler’s farm, and we soon struck an agreement. Uncle Bruce Kougher gladly hauled it home for me with his V200 International tractor and lowboy trailer. Great!!”

“But now I had a two-week break before I wanted to start hauling, so my Dad and I attacked the project (Figure 9). Get engine running and change all oils, rebuild hydraulic brakes, replace clutch disc, and paint. Long hours, but it was ready!!!”

Figure 9: Earle & Paul working on the 1946 Reo, 1969.

“The first project was retrieving the Lima from near Parker, Pennsylvania (Figure 10). Success. Amazingly, the Reo proved to be very dependable and hauled so many heavy loads” (Figure 11).

Figure 10: Lima engine on the 1946 Reo, 1969.

“Completing my internship, I returned home to open a General Practice in Brookville, Pennsylvania, on July 1, 1970. It was just ten miles from home. Medicine was so different then; I had my own patients, saw them when in the hospital, assisted when they needed surgery, and made house calls. After four years, I turned to Emergency Medicine and became one of the charter group of physicians at Dubois Hospital, remaining there until 1980, when Brookville Hospital opened their ER. I was Director there for 36 years, finally returning to general practice. Retiring In July 2020 after 50 years of practice, I now am devoted to the museum. It was a wonderful career.”

“After I returned home in the summer of 1970, John Wilcox and I continued to spend occasional weekends together and ranged farther to discover so many wonderful machines. Both our collections grew, and we frequently helped each other on difficult moving projects. Some years later, we decided to consolidate both collections in Coolspring. Little did we know what it would become!”

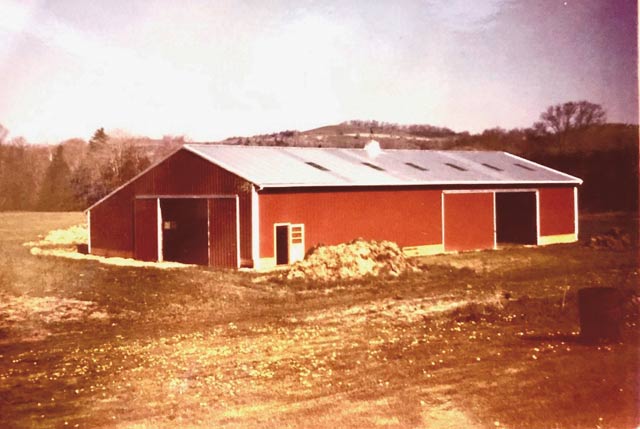

“In 1971, having even larger finds, I bought the “tilt bed” from Clarence “Red” Fisher who was a coal mine operator and early collector. The bed, now on the 1976 2070A Fleetstar, was originally on a 1956 S180 International. With Uncle Bruce driving one truck and my Dad helping, several big moves became possible. The collection was rapidly growing, necessitating the building of the Big Barn, now the Power Technology Building (Figure 12).”

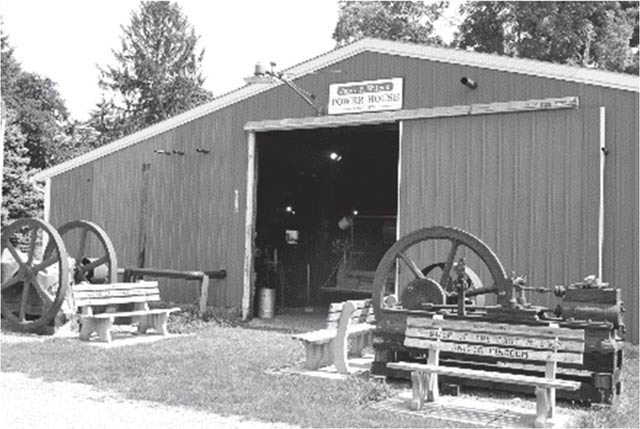

“John Wilcox was becoming more involved in Coolspring; so in 1976, the Power House (Figure 14) was built to house some of his engines, as well as mine. John and I were quite satisfied to have a large playground, but that was not to happen.”

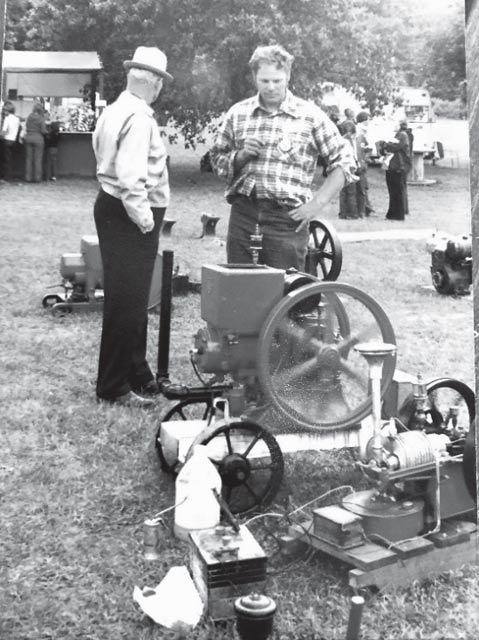

“A few years earlier, a patient of mine, John Kline, suggested during a visit that an organization be formed to open the collection to the public and have shows. John was superintendent of the diesel shop of the Pittsburgh and Shawmut Railroad in Brookville. With excellent organizational skills, he soon formed the Coolspring Hit and Miss Engine Society, and regular meetings were scheduled. The first show was held in 1976 (Figure 13), being a great success. It was a Saturday and Sunday event with the few museum buildings open, a couple of exhibitors, and a food stand. Reflecting back, those little shows were so pleasant and personal. Something good was beginning.”

“Over the next few years, the Hit and Miss Engine Society was being overwhelmed by the growth of the shows. Already, a fall event was added to the June show. So, we decided it was time to form another organization, and in June of 1985 the Coolspring Power Museum was formed. The first meeting was held in my kitchen, and an informal group selected seven directors: Preston Foster, Mike Fuoco, Paul Harvey, John Wilcox, Vance Packard, John Kline, and Robert Vogel.”

Now, adding to Paul’s narrative, when the museum was formed, he owned over half the engines in the collection. Backing up a bit, during Paul’s private practice years, he and John Wilcox expanded the Engine House (Figure 7) to 24’ by 20’ in 1971 and, finally, 24’ by 56’ in 1973 to house their rapidly growing collection. They also added structures as pipeline companies downsized and modernized, selling gas engines for junk price at $18 a ton. As Paul related earlier, in 1971, the Big Barn — or what is known as the Power Technology Building today — was constructed (Figure 12). Two years later, the Power House, which would later be renamed the John P. Wilcox Power House, was built (Figure 14).

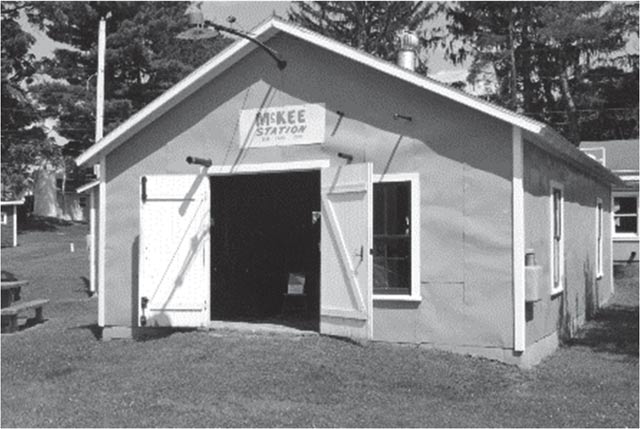

The Machine Works was constructed in 1974, and in 1975, Harvey and Wilcox acquired McKee Station, a 1939 National Transit Pipeline Station located south of Clintonville, Pennsylvania. They moved the entire building, stored it through the winter and re-erected it the following year (Figure 15).

Paul was well enough known by the bookkeeper at National Transit that he’d call up this guy and give him a serial number off this engine that was abandoned in place. And the guy’d say, “OK get it out, and when you get it out, give me another phone call and send me a check for $50, and I’ll take it off the books.”

Many of the engines that Harvey and Wilcox salvaged and relocated to Coolspring had escaped scrap drives through two world wars and sat abandoned, ripe for the picking. Their collection grew quickly (Figure 16), and other collectors came from miles around to see it.

Paul loved just about anything mechanical. And he loved his International trucks. He related an interesting truck story. Paul wrote, “Over the years I had been using my faithful 1956 International S180 truck with its massive, homemade hydraulic tilt bed and winch for all my engine hauling needs. It had a five-speed main transmission and a three-speed auxiliary, so I never ran out of gears. It all worked so well, but I frequently had to do minor repairs on the way. Its 308 cubic inch gasoline engine was always working to its maximum. I soon learned to carry points and condenser, as well as a few fuel filters in the glove box. Adding an electric fuel pump in series with the mechanical pump relieved the vapor lock in hot weather. With 12 or 15 tons on its back, it always came home, but it was so, so slow.”

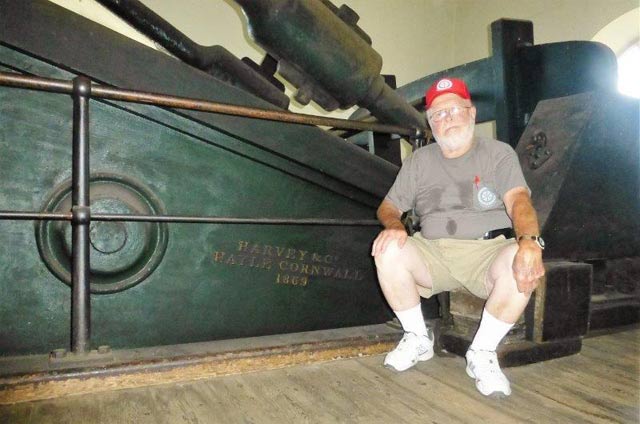

“Probably its most memorable load was moving the huge railroad wheel lathe from the Pittsburgh and Shawmut Railroad shop in Brookville to the museum. Wow, 44,000 pounds on the bed of a truck equipped with rear axles rated at 28,000 pounds! I kept the three-speed auxiliary transmission in its lowest gear, and was able to shift a bit in the main transmission. But I finally got it home seeking out all the back roads to creep along. The lathe is now in the Ford Museum Railroad and one of the few in the country that can turn steam engine drive wheels, which they do for other railroads. I am happy that it was preserved.”

“By 1991, it was apparent that I was a hazard on the road when loaded. Back in 1971, all trucks pulled down on the hills, so I could basically keep up. But as the years passed, its demise was inevitable. Pulling Clarington hill at 8-mph bringing home the 12-ton Blaisdell made the decision! (Some claim that he was passed by an Amish horse and buggy!) So in 1991, I decided to find a more modern chassis to mount that indestructible bed upon. I finally found a 1976 2070A International Fleetstar near Pittsburgh. Cab and chassis; just what I wanted! Driving it home with its 290 Cummins and nine speed was a joy. A new world had been opened!”

“My friend, the late Smokey Mumford, suggested that I bring both trucks to his shop near Brookville to make the bed change, which I readily accepted. After more work than we both anticipated, I finally had a great engine mover that could keep up with the best on the road. Driving a diesel and a nine speed was a new learning experience for me, but very enjoyable. The new ‘tilt bed’ has moved so much for the museum, including all of the 600-horsepower Snow except the main frame. Each trip has its own story.”

“The old S180 is still proudly here, owned and restored by Stewart McKinley. All can see it at the museum History Day’s truck show. And the new “tilt bed”? Well, it’s still working, recently making a trip to deliver an engine to a member near Warren, Pennsylvania. That’s why I love those Internationals!”

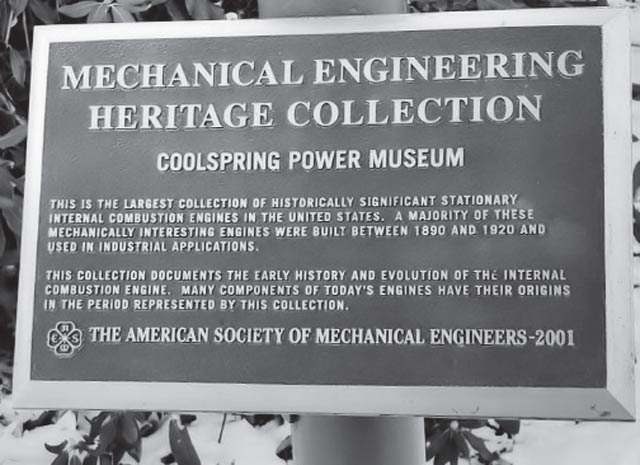

Today, Coolspring Power Museum features over 275 engines

— many of which are permanently mounted and operational — housed in 35

buildings and outdoor displays. In 2001,

The American Society of

Mechanical Engineers designated the museum as a

Mechanical Engineering Heritage Collection and presented it with a

plaque (Figure 17) that states, “This is the largest collection of

historically significant stationary internal combustion engines in the

United States.” Paul put almost all of his money into that collection

and the museum. He was primarily responsible for bringing dozens of

large displays into preservation here, including McKee Station, Windy

City Air Plant and the 300-horsepower Miller engine. However, the crown

jewel among his acquisitions is a 175-horsepower Otto engine with

10-foot flywheels that once powered the Water Works in nearby

Brookville, Pennsylvania.

Wilcox originally purchased the 25-ton engine and 20-ton Deane pump for $1. Then, he spent most of 1969 dismantling them and hauling the parts — except for the engine’s main frame, which required special trucking — to his home near Columbus, Ohio. However, he never got it re-erected, and when his health started failing 35 years later, he sold it to Paul Harvey who moved it to CPM. The Otto engine was one of only five built and possibly the only one left in existence. It’s one of the largest single-cylinder gas engines in the world. It is reassembled, in running condition and on display at CPM, sitting on a 20-by-10-foot foundation, roughly 9 miles from where it worked its entire life (Figure 18).

College was the only time Paul lived outside of Coolspring. As his narrative told you earlier, he only stayed in private practice for four years before he became an employee of Brookville Hospital and directed their emergency department for the next 36 years. Long time friends said that “He really did have a big heart, and he really cared about his patients more than the average doctor. His private practice failed miserably because he was in a fairly poor area and his patients wouldn’t pay him. He would never go after them for the money, ever. He never even considered it.” Even after Paul started working at the hospital, it was said that he never turned away a resident of Coolspring who showed up at his house needing help.

Paul Harvey’s generosity toward his neighbors didn’t stop at his medical practice. He purchased the Coolspring General Store two different times from 1977 to about 2009 to preserve its history and maintain a meeting place for the community. In between, he sold it to Lorraine Hilliard, who owned it from about 1980 to 1993 and worked there as an employee for the duration of Harvey’s ownership both times.

He never made money owning the store. Sometimes he lost money — his idea to sell penny candy at two pieces for a penny wasn’t lucrative, and he couldn’t have been making out on the fabled 9-ounce ham and cheese sandwiches he sold at the store. Owning the store, like so many other endeavors, wasn’t about making money for Harvey. He bought the store to preserve the oldness of it.

When he owned the store, he fixed it up the way it had been when he was growing up. He oiled the wood floor annually. He repaired the big pot-belly stove that heated it, having a new bowl cast for the bottom. Walking through the front door, customers were welcomed by the large pot-bellied stove directly ahead. On either side of the stove, sat wooden benches where customers would sit and share town news. To the right, the penny candy counter featured old glass countertops and glass jars filled with candies. To the left, the post office rented space. And when the store wasn’t doing well, he paid his employees out of his own pocket.

While Paul Harvey’s collection is the foundation CPM has built off of for the last 40 years, it’s far from his only contribution to the displays here. He took a special interest in the Pennsylvania oil fields and obtained a lot of engines that were built locally. He spent considerable time researching their history in Butler, Erie, Franklin, Pittsburgh and Oil City to make display plaques for museum engines, as well as to write articles about their history for Gas Engine Magazine, The Flywheel, Bores & Strokes, and several local newspapers. He spent days tracking down information on these engines, working with historical societies and combing through microfilm of small-town newspapers. In some cases, he and Wilcox were even fortunate enough to hear the history of the acquisitions firsthand. They were early enough into the collecting days that a lot of the very old timers that were still working in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s were able to share some of the actual stories of using and dealing with this equipment.

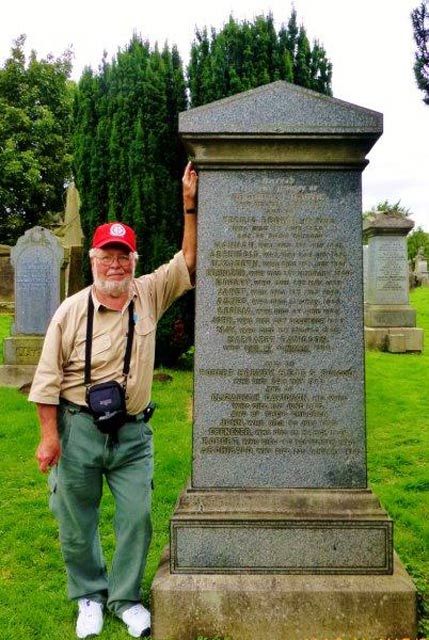

For the most part, Paul was driven by his passion for preserving the history of Coolspring and the rich engineering feats in oil and natural gas fields, hotels, trolley stations, utilities and farms across western Pennsylvania. But he also enjoyed trips across the United States and Europe in search of unique engines. Tom Rapp recalled travelling many tens of thousands of miles driving across this country, visiting 48 of the 50 states with him. Rapp and Harvey trekked across the country and beyond for over 30 years, chasing antique internal combustion engines and steam engines.

One of Paul’s last acquisitions was the Graz Diesel — the oldest operational Austrian-built air blast diesel in the world. The engine (Figure 19) was offered to him following a trip to the city of Hof in Bavaria, Germany, in 2019, to learn how to operate CPM’s Augsburg air-blast diesel engine from an expert. Upon completion, the Augsburg will be the oldest operating diesel engine in existence. Both engines, along with a Benz diesel, are being reassembled in the museum’s new Diesel Centrale CPM building that was Paul’s dream.

As he was with so many of his projects, Paul was passionate about Diesel Centrale CPM. I think, in his heart of hearts, he also realized that his days of being able to enjoy his lifelong passion were numbered. And that sometimes led him to want to bite off a bigger chunk than the museum was able to digest as quickly as he thought we could. Figure 20 shows Paul in May 2018 clearing the area where the Diesel Centrale CPM building now stands. Paul was really proud of this collection and he lamented the time it has taken to get this building and display completed – a story for another time! I’m sure he’ll soon look down with a great smile when those vintage diesels come back to life.

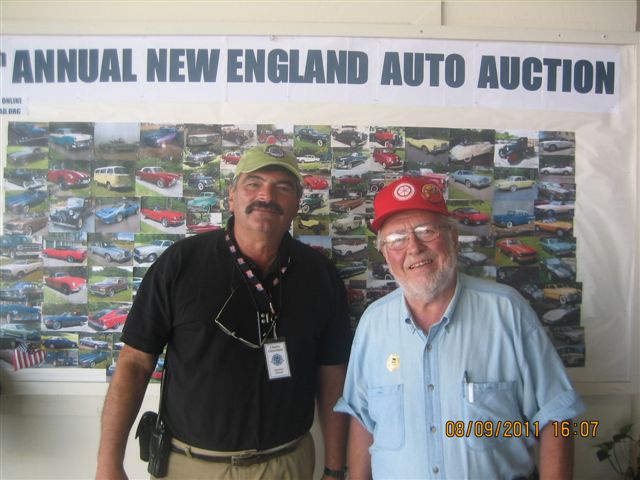

One of Tom Rapp’s favorite trips with Harvey was to Stirling, Scotland, where Paul tracked his lineage to a cemetery near Stirling Castle. They also visited Yellowstone National Park five times together. Rapp recalls the trips being both enjoyable and educational, noting Paul’s uncanny ability to “always find something out there that was weird and unusual”. Paul was very much involved in CPM up until the end of his life. He completed one final term as museum vice-president in 2024, and he continued to write articles about the renovation of his family’s old chicken house as a place to display some of his smaller engines and other items in his collection. He celebrated his 80th birthday last summer and was recognized at last year’s June show with his wife, Marilyn (Figure 21). Accompanied by Tom Rapp, Paul also celebrated his birthday with a cruise of the lower Mississippi River last July (Figure 22).

Figure 22: Paul & Tom on Mississippi River cruise, July 2024.

Dr. Paul Harvey led an interesting life with a unique interest he followed near and far. In some ways, he lived his life in a time capsule, surrounded by the belongings of generations of his family in his childhood home and surrounded by generations of antique internal combustion engines at CPM. Unlike the famous journalist and newsman who shared the same name, Dr. Paul Harvey would have never fit into big city life, but he fit perfectly at Coolspring. His friends joked about what patients may have thought when he went to work at the hospital on Mondays with grease on his hands. But people come from all over the world to experience the collection he helped put together on what used to be his family’s farm.

Paul passed away on February 19, 2025. He is laid to rest just a few miles from Coolspring in Ohl Cemetery, with his father Earle, mother Arlene, aunt and uncle, Dorothy and Bruce Kougher, his grandfather Horner, and other ancestors.

One of Paul’s last trips with Tom Rapp was to Paradise, Pennsylvania, to take pictures for the last column that he submitted to FARM and DAIRY in 2025, which he fittingly signed off, “From Paradise, Paul” (Figure 23).

We’ll miss you Paul, but we know you’re in good hands and we’ll do our best to carry on your legacy at the Coolspring Power Museum!

The Paul Harvey Memorial Fund has been established for a proposed larger CPM gift shop and/or a new welcome center that will be dedicated in Paul’s honor. Donations may be made in Paul’s memory to the Coolspring Power Museum at any time.