May 2022

Finally!

The First Commercially Successful Gas Engine

By Paul Harvey

The gas engineís humble beginnings date back to 12th century China when

the cannon was invented. Already

having produced gunpowder, a weapon was not a surprising use of their

new explosive. The cannon worked

well and was built in many sizes and configurations.

But all had two things in common:

a barrel and a projectile. Seems simple!

Hmmm. Many years went by, but

gradually thought was given to peaceful and useful adaptations.

Now letís see; that barrel could

become a cylinder, and the cannon ball a piston.

So, the inventors went to work to

construct some mechanism to make a piston go back and forth and hook it

up to make rotary motion. Centuries

went by before it happened.

Now letís jump ahead to the 1700s. Gosh,

thatís 500 years from that innovation of that cannon.

But an era of enlightenment had

awakened with the great Industrial Revolution dating about 1760 to 1840.

So much invention had already

started in the early 1700s. Finally,

that cannon barrel and ball was put to productive use!

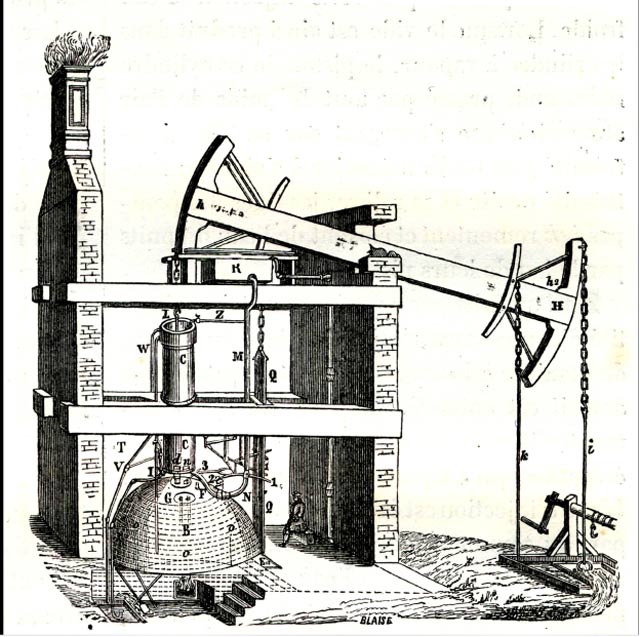

In 1712, Thomas Newcomen, of England, developed the first commercially

successful engine to use the piston and cylinder.

It produced a reciprocating

motion that was widely adapted to pump water from mines.

Operated by steam, it burnt wood

or coal for its boiler.

By 1763, James Watt invented the connecting rod and crankshaft to

provide a rotary motion. The

modern steam engine had been invented! Now,

what next?

During the Industrial Revolution, a prolific amount of invention took

place. The early and mid-1800s

saw a concentration on the internal combustion engine.

Why burn the fuel externally to

make steam when it could be burned directly in the cylinder to make

power? Good idea, but how to make

it happen? So many ideas and

prototypes, but they all had problems. None

reached commercial success.

But wait! In 1860, a

Belgian-French engineer, Etienne Lenoir, succeeded.

He built the first commercially

successful gas engine! Here is

his story.

Jean Joseph Etienne Lenoir was born on January 12, 1822 in the village

of Mussy-la-Ville, then a part of Luxembourg.

He was the third child of eight

whose father was Jean-Louis Lenoir, a merchant, and whose mother was

Margot Megdelaine, a housewife. He

left the tiny village of 800 souls at an early age, destined to become

an inventor, and worked as a farm hand on his journey to Paris. There,

he worked as a waiter and became interested in electricity.

By much self-study, he became an

accomplished engineer. Turning to

the gas engine, he had a running prototype built in 1858 and was granted

a patent for it in 1860. It was a

commercial success, and although fuel inefficient, many were sold throughout

France and put to useful work. By

1864, over 130 were working in Paris itself.

Total production was about 500

engines and a German license had been issued.

His destiny was fulfilled.

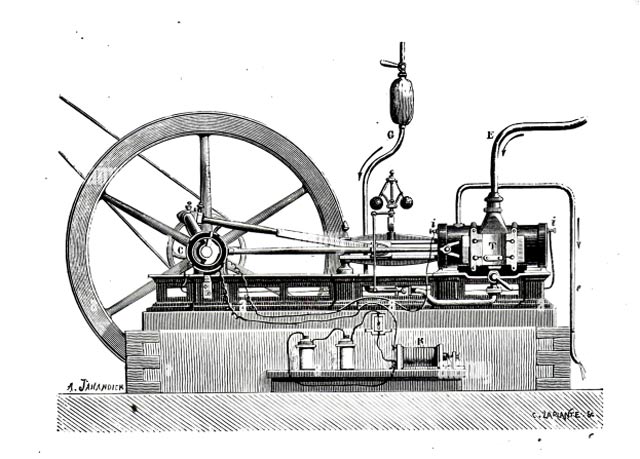

Beautiful machine, but how does it work?

Well, itís quite simple to us now but very advanced for its

time. At that time, the Otto

cycle of compressing the charge was not invented yet; it had to wait

another 20 years. So, it was a

non-compressing two-cycle engine. But

he made it double acting, so it fired on both sides of the piston.

Hmmm, could create a cooling

problem so plenty of water had to be flowed through the cylinder.

Double slide valves, one on each

side of the cylinder, were used for the intake and exhaust functions.

Refer to the following

illustration.

Pipe G is the gas intake and pipe E is the air, mixing and introduced

into the cylinder by the slide valve shown.

A similar slide valve for the

exhaust function is on the other side of the cylinder.

It worked very well.

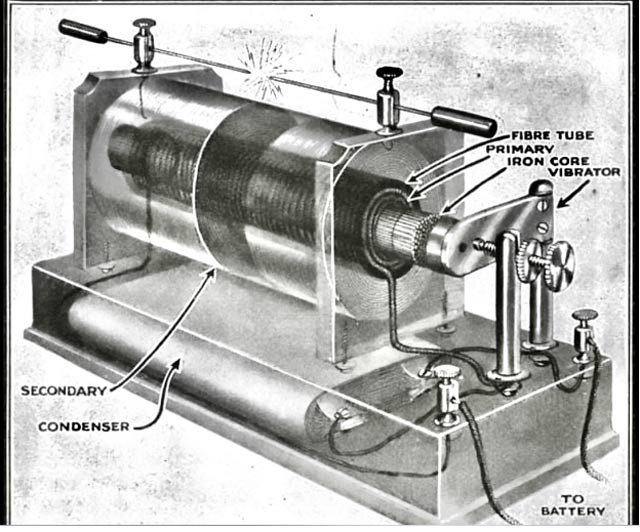

But what is the device shown along the engine base?

Yep, itís a coil and batteries.

In 1858 Lenoir invented the spark

plug, calling it ďjumping sparks.Ē He

used the newly invented Ruhmkorff

coil to do this!

Invented by Heinrich Ruhmkorff, the coil is known to all engine

folks as a ďbuzz coil.Ē Henry

Ford used them for his Model T ignition.

Sadly, Lenoirís use of the spark plug was abandoned in favor of

open flame ignition and hot tube ignition for so many years.

Lenoir was truly a genius and

built a wonderful machine.

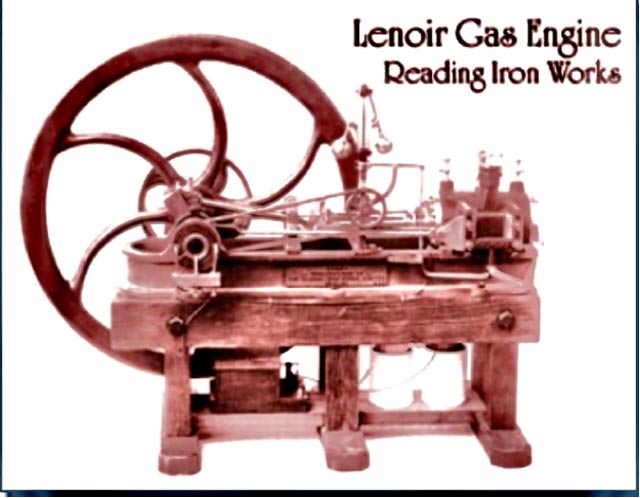

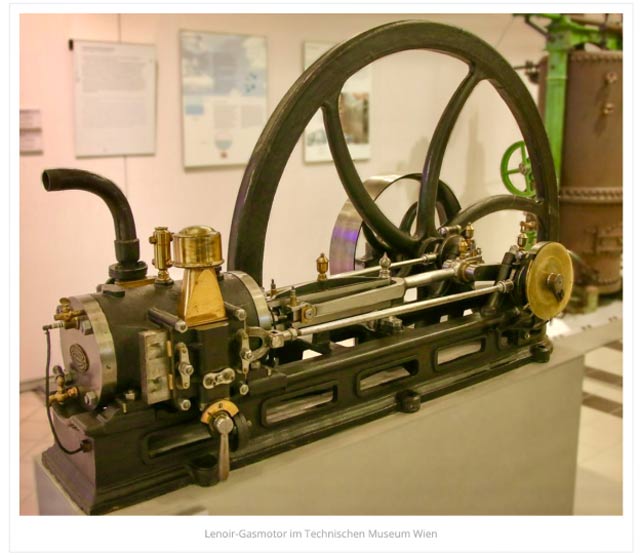

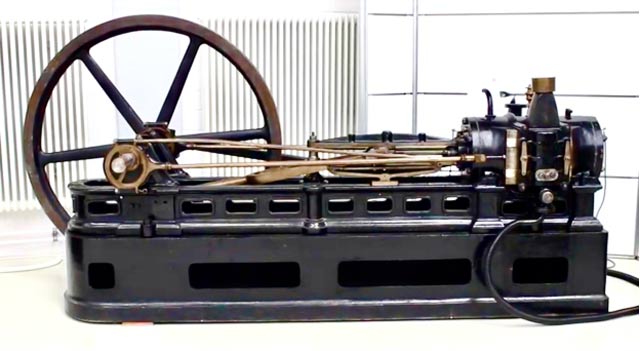

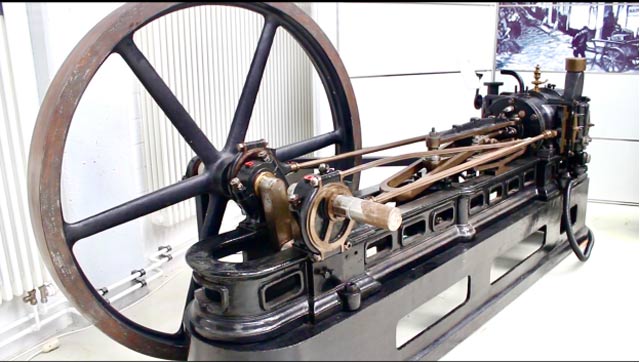

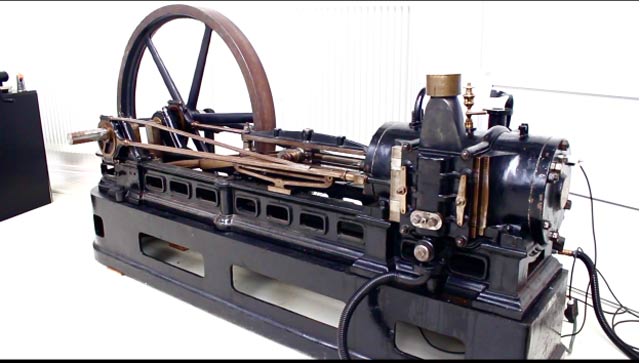

Here are three views of the Lenoir engine in Deutz Technikum in Cologne,

Germany. It is operated for the

museumís many visitors.

Note the two slide valves, operated by eccentrics, located on either

side of the cylinder, and the spark plugs for ignition.

Amazingly, these engines were

built to 20 hp!

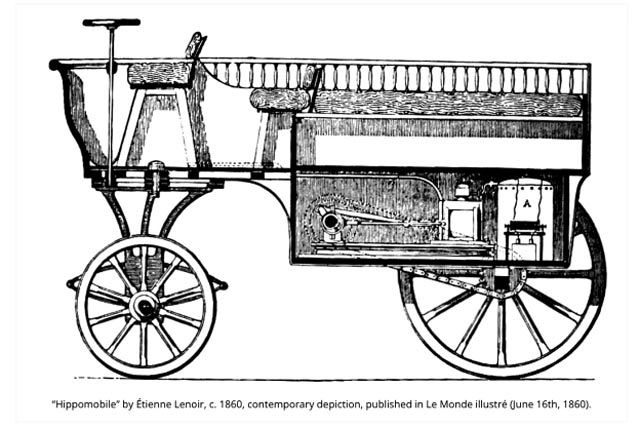

But Lenoir was not satisfied with stationary engine.

He built an automobile!

Yep, his car, the Hippomobile,

was on the road in 1863. He

installed a 1.5 hp version of his engine into this tricycle frame and

used liquid fuel by a primitive patented carburetor.

It covered the seven-mile course

from Paris to Joinville-le-Pont and back in 90 minutes, at the breakneck

speed of 3 km/hr. Slow, yes, but

it was successful! A new era had

begun.

He still was not satisfied so he turned to motorboats.

Installing an improved version of

his engine in a 12-meter-long boat for a Mr. Dalloz, it was used on the

Siene River for the next two years.

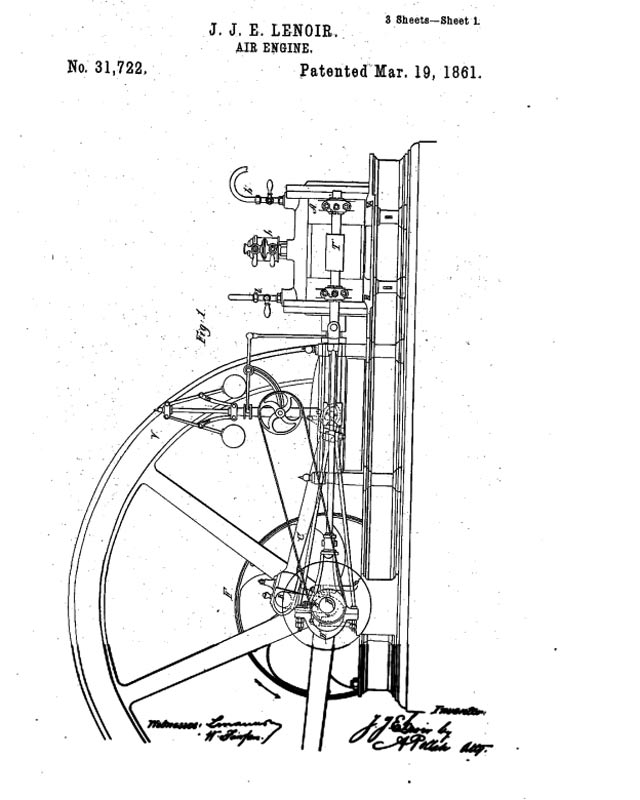

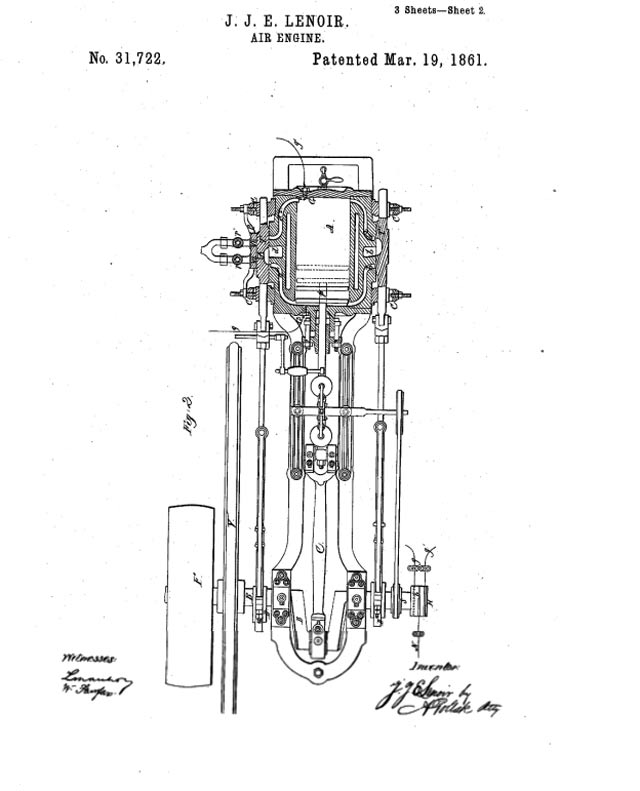

These two images from Lenoirís US patent illustrate how the engine

operated. The reader can access

the

entire patent on Google Patents. The

engineís design is graceful and very pleasing, and was copied for future

generations of engines.

The two slide valves are illustrated as well as the graceful governor.

It was a job well done!

Lenoir spent the rest of his life in peaceful prosperity in his

apartment in Paris. He often went fly fishing in the nearby Seine, but

remained active and followed the further development of the combustion

engine with interest. Jean Joseph

Etienne Lenoir quietly passed away on August 4, 1900.