January-February 2019

Sir Dugald Clerk

By Paul Harvey

Does the above name ring a bell with you? Hmmm? Of course it does - gas engines! He's the gent who invented the Clerk cycle of engine operation. And who was the major maker of that type of engine in America? Joseph Reid. So now it all comes together for you. But for this article, we are going to journey "across the pond" to Scotland and see what we can learn about this most interesting individual. It will be a good story.

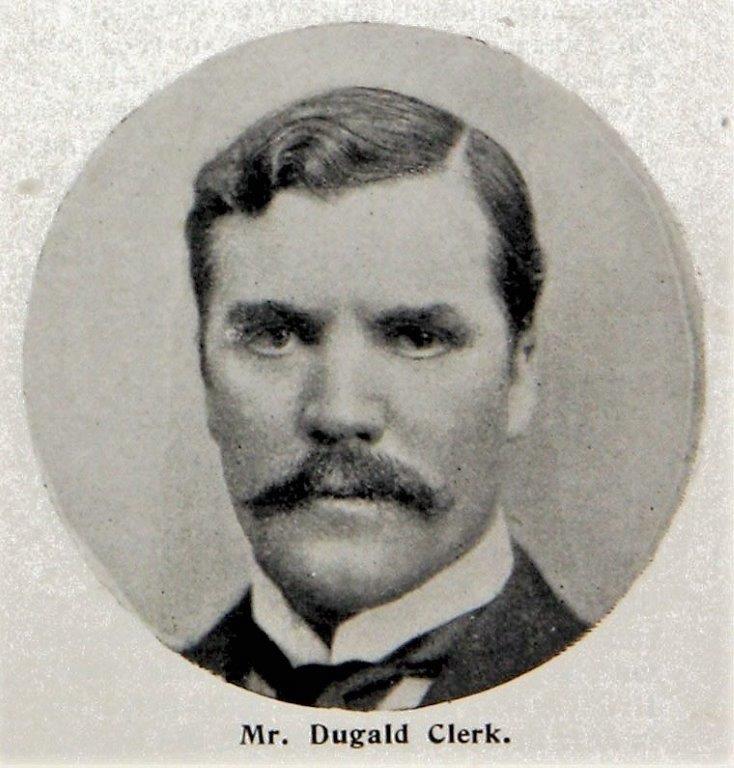

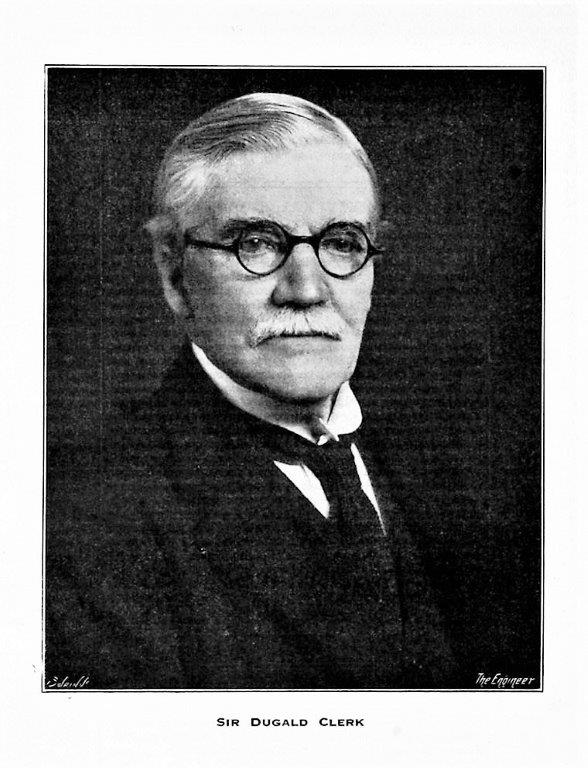

Clerk was definitely a unique and gifted person. He was intelligent, diligent, and thoughtful. Although his career developed into many different areas, he never forgot his love for the gas engine and he was always eager to learn more. His 1904 portrait is seen in Photo 1. Most interesting is that Clerk enjoyed being one of the very early pioneers in the birth of the gas engine and lived to see it become a successful, everyday machine. Few others were given that pleasure.

Using our time machine, we will travel back to 1819 and find that Donald Clerk was born in Argyle, Scotland, which is a rural area very near to the city of Glasgow. Donald had a mechanical inclination and soon opened a blacksmith shop. Tools were crude then but he persevered and became a Master Blacksmith, which is somewhat similar to today's machinist. By 1871, he and his wife were living in Glasgow and his works employed five men and ten boys! He and his wife had a large family of ten children, Dugald being the oldest. Donald passed away in 1880 at the age of 61. I'm sure that he must have been proud of his son, and it is sad that he did not live to see Dugald's many honors.

Have any idea what it must have been like to live and work back then? I'm sure it was very different than today! This was the Industrial Revolution! It lasted essentially from 1740 to 1880. The world was changing, and one had to change to keep up with it. The pace must have been hectic. Manufacturing was transitioning from a "cottage industry" into huge factories. There were inventions galore including the cotton gin, the power loom, the sewing machine, the spinning jenny, the locomotive, and the steam engine just to name a few. Glasgow must have been busy, but dirty. Factories sprung up, powered by crude steam engines whose boilers spewed forth black sooty smoke. So, amidst that environment, Dugald saw an opportunity!

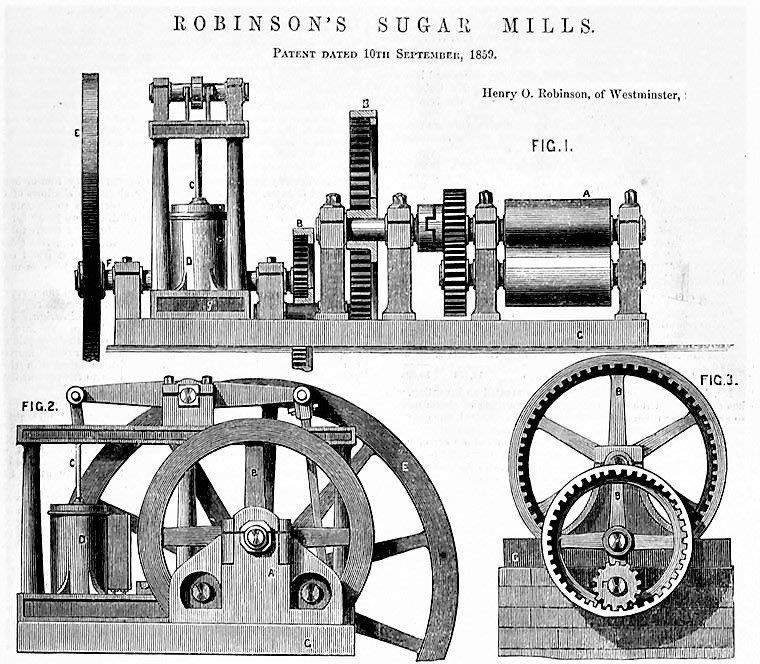

Dugald Clerk was born into this scene on March 31, 1854. He was born in dirty, bustling, prosperous Glasgow, and he certainly made the best of it. At age 14, he entered apprenticeship at his father's works. That was 1868, and he began learning the trade. He also apprenticed at the works of H.O. Robinson and Company in Glasgow. It is interesting to note that Henry Robinson started making sugar processing machinery in 1843. Photo 2 shows a preserved 1843 installation at Belle Vue Harel on the island nation of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. Robinson's 1859 patent is seen in Photo 3. Pretty crude, but it worked. Dugald's apprenticeship ended in 1871.

I wish to take this opportunity to mention that I have searched many sources for the material used in this article. I have found some notable differences between them and have tried to choose the source that is most commonly used and which makes the most sense to me. This material is as accurate as I could make it.

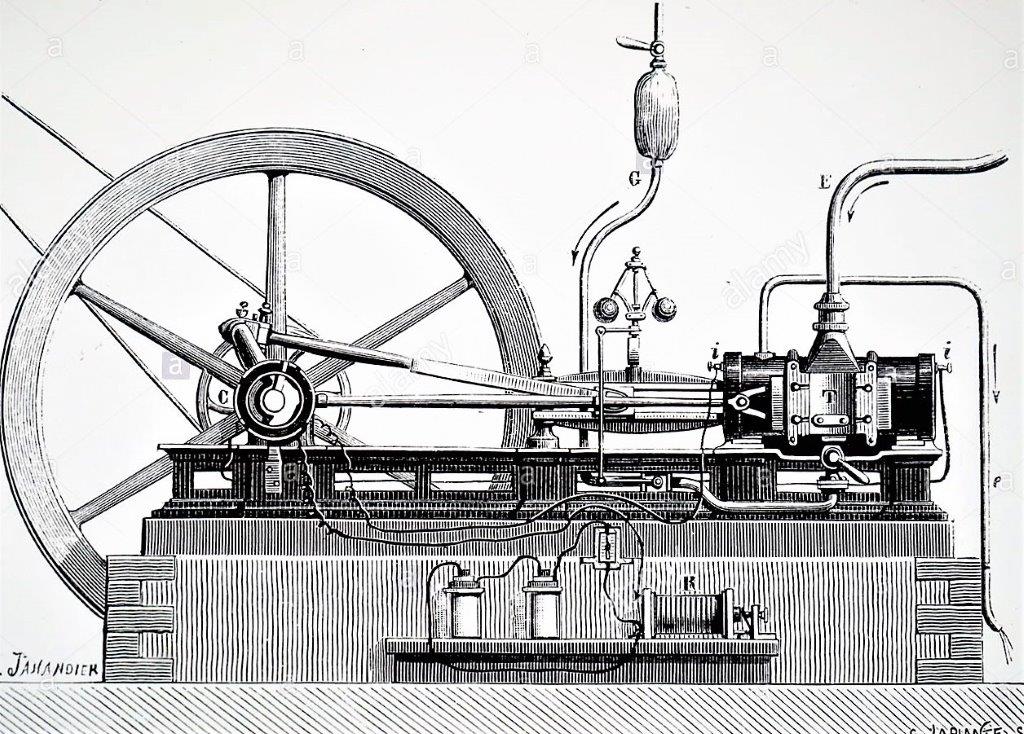

From 1871 through 1876, Dugald studied chemistry and physics at both Anderson College in Glasgow, and at Yorkshire College of Science in Leeds. During that time, he happened to see a Lenoir engine operate at a joiner's shop in Glasgow, and a lifelong love affair with the gas engine was born. Etienne Lenoir, a Belgian engineer, patented the first successful gas engine on January 24, 1860! See Photo 4. This engine was in actual production and was successful for its time. Its failure was its excessively high fuel consumption, due to its non-compressing design. In essence, it was copied from a double acting steam engine, even to its slide valve. Amazingly, Lenoir chose high tension ignition and invented the spark plug! Many, many years lapsed before spark plugs were in common usage.

Dugald actually built his first gas engine in 1876 in his father's shop. This engine was really a modified Brayton engine, and he was trying to add compression to it for efficiency. Dugald was meticulous in using complicated mathematical calculations for his designs, and he had a deep understanding of thermodynamics as well. It is notable that 1876 was the year of Otto's patent of the four-stroke cycle engine. Dugald did produce a true compression engine in 1878 which developed three BHP at 200 RPM. It was exhibited at the Royal Agricultural Society's show in July 1879. Unfortunately, there are no illustrations of these two machines.

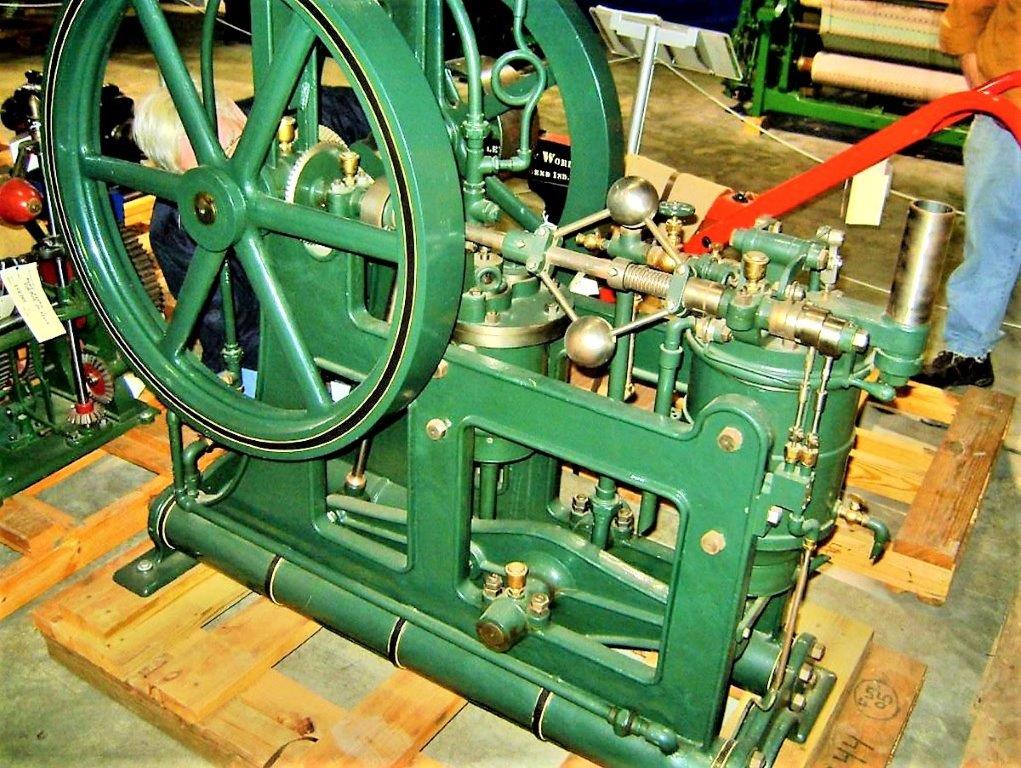

George Brayton (1830-1892), a gifted inventor, foresaw an engine with

the combustion inside the cylinder, unlike the steam engine with its

external combustion. Hence, he envisioned the internal combustion

engine! Born in Boston, he started experimenting with internal

combustion in the 1850s. In 1872, he patented his "Ready Motor,"

so named because it could be started immediately and did not need time for a boiler to

heat and produce steam. The Brayton was a constant pressure

ignition engine. It had two cylinders: one an air pump, and the

other a combustion cylinder. The fuel mixture passed through a

metal mesh between the cylinders and was ignited by a constantly-burning

pilot flame. The flame would not pass back through the mesh and

cause havoc in the pump cylinder. Why not? Recall the mesh

in the spout of a safety gasoline can! The main combustion then

burned for the entire outward stroke of the piston at a constant

pressure, and not as an explosion. See Photo 5.

These engines were quite popular and noted for their smooth

operation and easy starting. In 1878, Dugald Clerk modified a five

horsepower Brayton by giving it spark ignition. Hmmm! Sounds

like he's on to something good!!

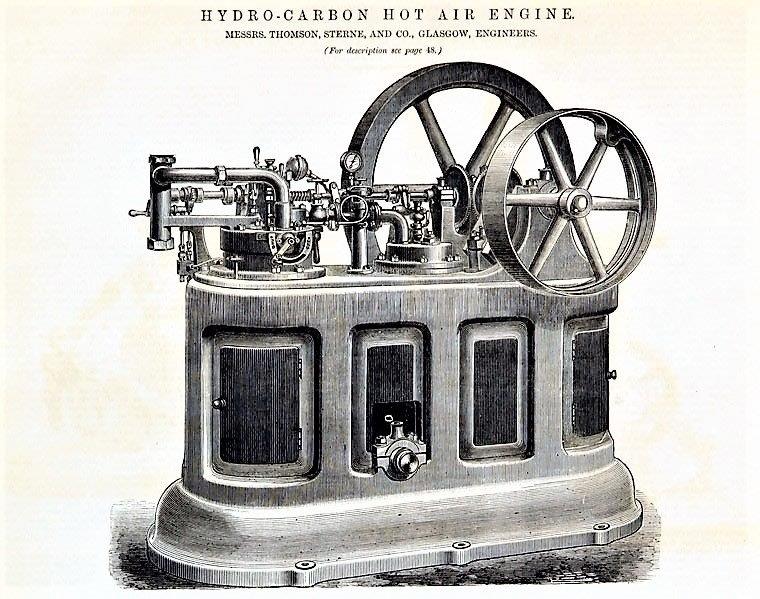

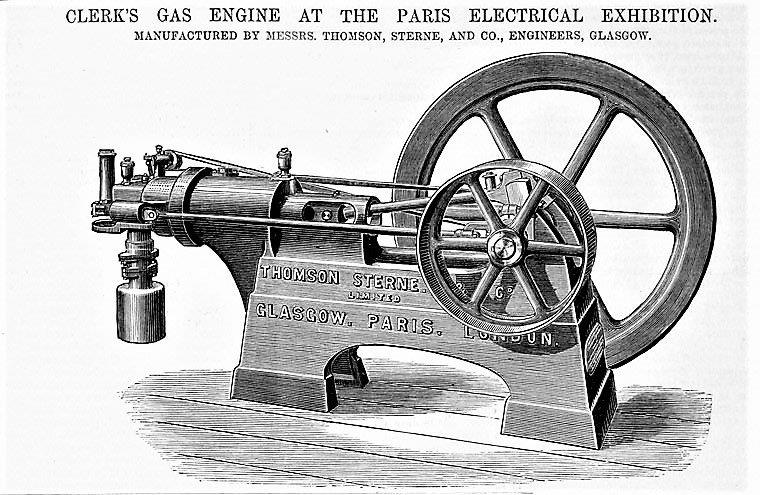

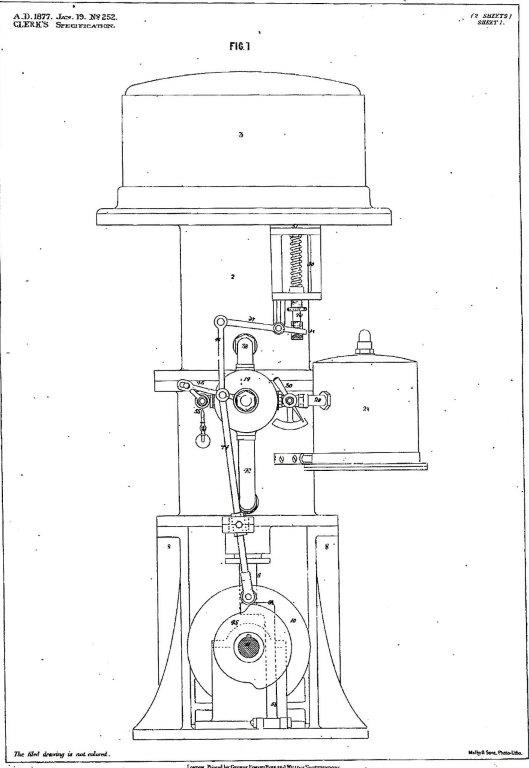

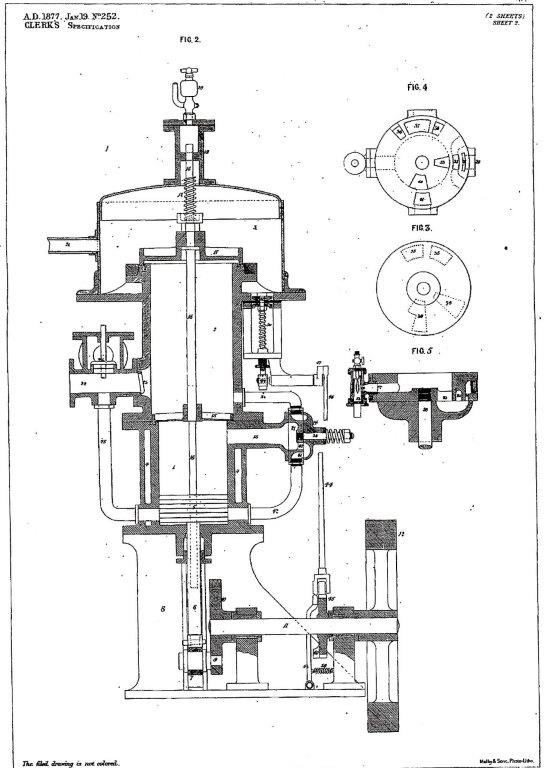

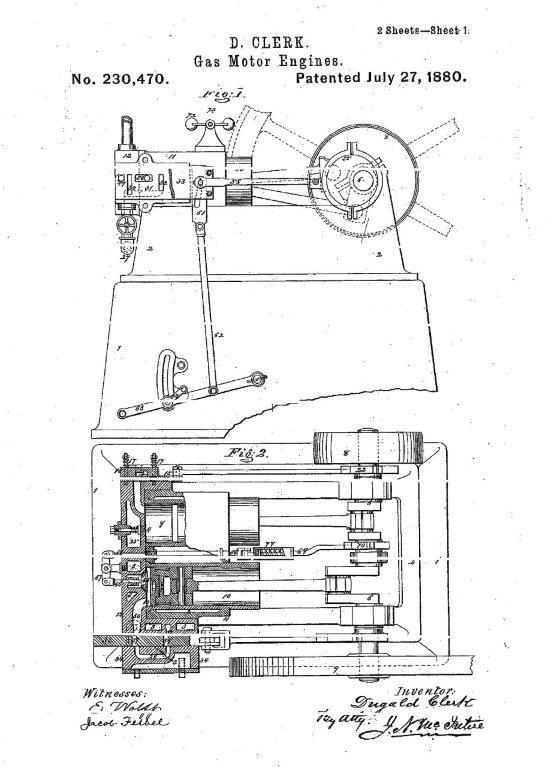

Clerk was granted over 20 patents during his long career, most concerning the gas engine. The illustrations from his 1877 patent are shown in Photo 8 and Photo 9. His one American patent of 1880 is illustrated in Photo 10. All three of these engines seem crude but definitely show progress. It is quite interesting to note that Dugald chose not to enter into the production of his engine but let someone else do it. Smart! He could gain the profits, but not be concerned with the business end and actual production. He happily could devote all his to time tweaking his design. During that period, he resided at 42 Dalhousie Street in Glasgow. Note the modest home in Photo 11. No, I don't think the blue car was his!

So just what is the Clerk cycle? Dugald set out to make an efficient engine and, to do so, he wanted it to have a power impulse on every revolution of the crankshaft, hence the two-stroke cycle. In contrast, the Otto engine had a power impulse on every second revolution of the crankshaft, making it the four-stroke cycle. So he studied other earlier engines and was especially impressed with the Brayton. It had two cylinders but no compression. Hmm! How could he make it better? It slowly evolved, but he did it! Let's see how.

Clerk made an engine with two cylinders and two pistons. The pistons were placed 90 degrees out of phase with each other. One piston, the charging one, drew in the gas and air mixture through an automatic intake valve. On the charging piston's return stroke, it pushed the mixture through an automatic crossover valve. The fuel now entered the power cylinder from the head end, while the exhaust gases escaped through openings or ports in the cylinder wall. In essence, it was a "uniflow" engine with the fuel entering one end of the cylinder and the exhaust passing out the other end. This arrangement minimized the possibility of diluting the incoming charge with the spent exhaust gases. The power piston then proceeded forward to the head, causing compression and, near top dead center, ignition took place. And so the cycle was repeated. Simple, huh? He got power on every stroke of the piston. The Clerk cycle! It was very successful.

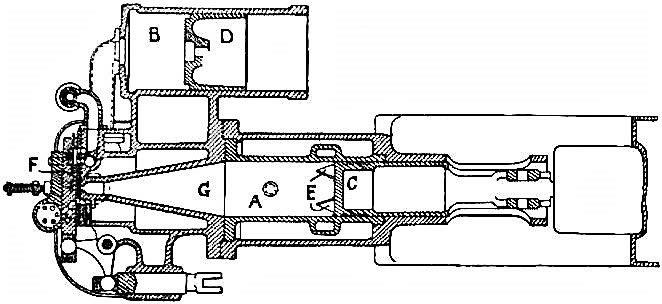

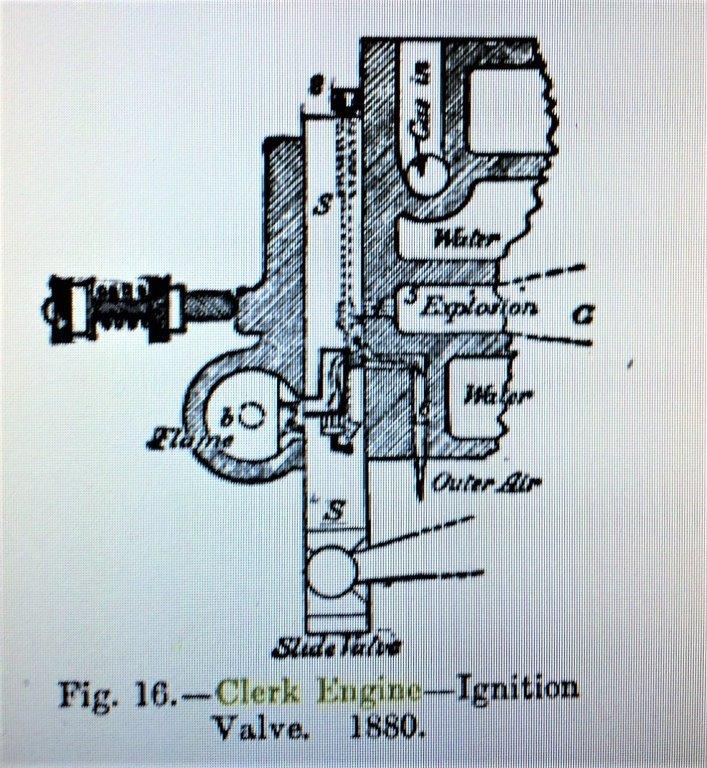

So now, let's take a look at some early illustrations of his engine. Photo 12 is a longitudinal cross section of the Clerk engine cylinders. B is the charging cylinder and D is the charging piston. Note that the charging cylinder is not cooled, while the power cylinder, A, is cooled. The charge is delivered into the power cylinder, A, through valve F. In this case it is a slide valve using open flame ignition. G is the combustion space. The exhaust escapes through ports, E, and the power piston is C. When asked, Clerk denied any attempt at supercharging and stated the charging piston is for fuel transfer only. Sounds confusing, but really it's quite simple. Photo 13 is a detail of the ignition valve.

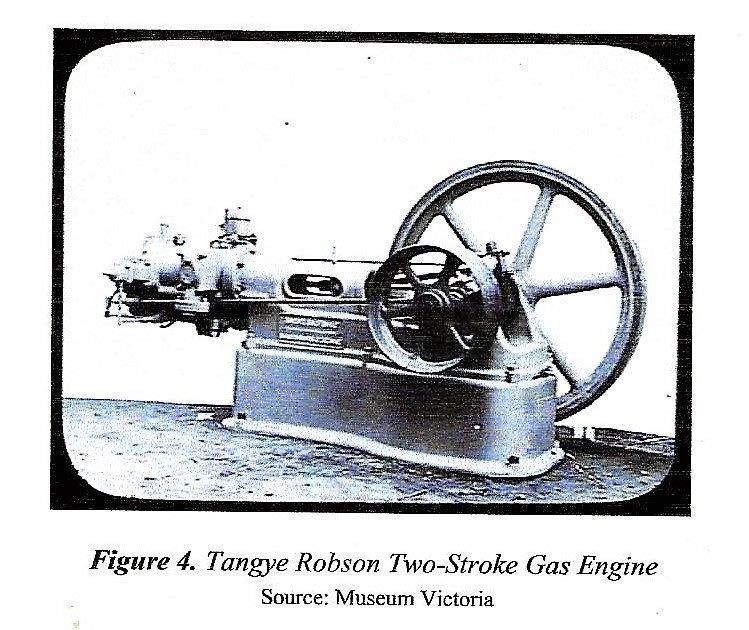

Upon leaving Thomson, Sterne, and Company, he joined Richard Tangye's firm in 1886, and moved to Birmingham, England. Tangye (1833-1906) was from Cornwall and became a mechanical engineer, manufacturing engines and all sorts of heavy equipment. One specialty was hydraulic equipment focusing on lifting jacks. His jacks launched the ironclad sailing steamship, the SS Great Eastern, in 1858. It was the largest vessel built at that time and measured 705 feet long and weighed 17,274 tons. Tangye's motto became, "We launched the Great Eastern, and she launched us." Clerk's job with Tangye was to improve the 1877 two-cycle engine designed by James Robson. See Photo 14. This two-cycle engine was much like the engines used in the American oil boom. It only had one cylinder which produced power on the head end of the piston and scavenged behind the piston. Clerk succeeded in making it successful.

In 1888, Dugald entered practice as a consulting engineer in Birmingham. Soon, he partnered with Sir G. Croyden Marks, another noted mechanical engineer. The firm, Marks and Clerk, prospered and consulted in all types of engineering problems. One speciality was patent litigation. It was recognized in 1911 as, "the greatest firm of its kind in the world." It still exists today with branches in all the major cities of the globe!

From 1892 to 1899, Dugald was the engineering director of Messrs. Kynoch of Birmingham. This firm was a major ammunition manufacturer and played an important role in World War I. Clerk designed the equipment to manufacture the various forms of munitions. During this time, he was also a consulting engineer to the Patent Shaft and Axletree Company of Wednesbury.

During his long and distinguished career, Clerk wrote four classic engine reference books: 1882, The Theory of the Gas Engine; 1894, The Gas Engine; 1897, The Gas and Oil Engine; and 1909, The Gas, Petrol and Oil Engine. He also authored many academic papers and was a lecturer in great demand. During his later life, he was awarded five honorary doctorates. In 1908, he was elected into the Royal Society as Fellow. He had many more honors that space does not permit to be listed here.

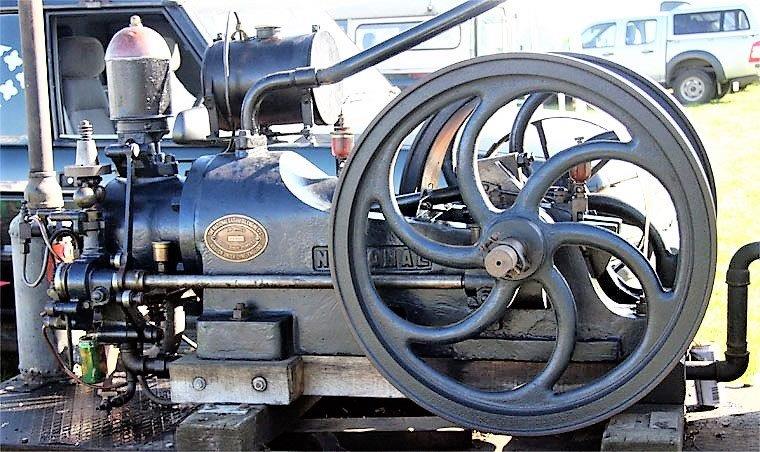

In 1902, Dugald became a director of the National Gas Engine Company located in Ashton-under-Lyne, England. There he took an active part in the design of this firm's engines. He enjoyed the freedom to further study thermodynamics and explore the uses of gas in heating and lighting. Photo 15 depicts a beautiful National of 1930 vintage. National was a huge firm which made a wide variety of engines. They produced multi-cylinder vertical engines into the 1960s. Clerk became the chairman of the firm in 1929 and he retained this position until his death in 1932.

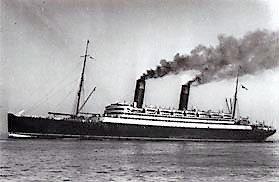

It is interesting to note that Dugald and his wife, Margaret, visited New York City in July of 1906. He was a consulting engineer and the purpose of the trip was business. They departed Liverpool, England, on July 3, 1903, and sailed on the RMS Caronia. See Photo 16. Their American headquarters was the Savoy Hotel. One wonders if he made a trip to Oil City, Pennsylvania, to meet Joseph Reid and study Reid's engine? Perhaps we will never know!

From 1916 through 1918, which was during World War I, Clerk served his country in many ways. He was the Director of Engineering Research at the Admiralty, a member of the Advisory Committee for Aeronautics at the Air Ministry, Chairman of the Internal Combustion Engine Sub-Committee, and a member of the Munitions Inventions Committee. He was also Chairman of the Water Power Committee of the Board of Trade. For all this fantastic work, he was created a Knight of the British Empire in 1917. Now he was Sir Dugald Clerk!

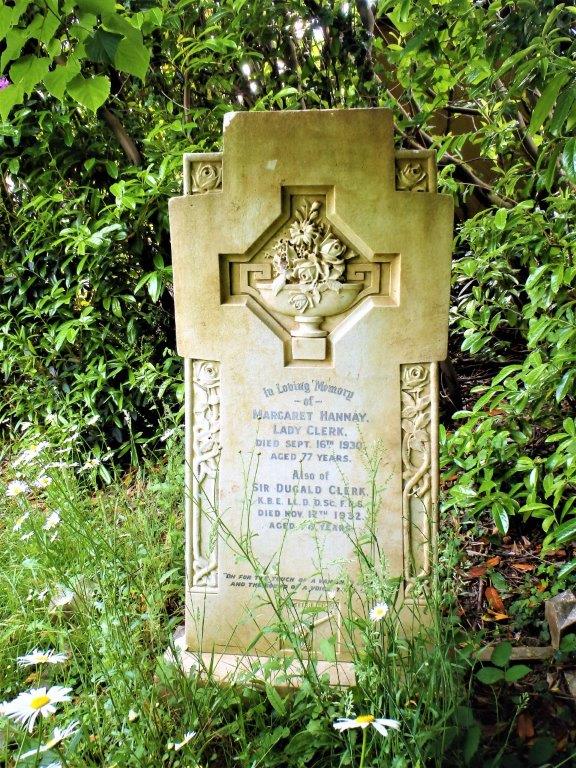

Sir Dugald never really retired but, due to some health issues, moved to the rural Ewhurst, Surrey, not far from London. Here he could design, consult, invent, or just plain relax, to his leisure. He certainly led a very full and fruitful life. He deserved all the honors bestowed upon him. Sir Dugald passed away at Ewhurst on November,13, 1932, and is buried in the St. Peter and St. Paul Anglican Church's cemetery. The church is seen in Photo 17. It is a very pastoral setting. The value of his estate was £54,412. The modest headstone is illustrated in Photo 18. The inscription reads, Margaret Hannay, Lady Clerk, and Sir Dugald Clerk.

Sir Dugald was born before the invention of the gas engine and grew up as the engine grew up. He played an important part in its development from the very beginning. He saw the infant mature into an important and powerful adult, and he helped it all the way. Apprenticed in the mechanical skills and educated in chemistry and physics, he loved to invent, calculate, design, build, and improve. That was his life! Photo 19 is his portrait in the year of his passing.

Some time in the future, I plan to write an article comparing Clerk and Reid, noting the similarities and the differences. I am sure there is more than a causal connection.

Photo 1: Dugald Clerk in 1904

Photo 2: Robinson sugar processing machine

Photo 3: Robinson's 1859 patent

Photo 4: Lenoir engine

Photo 5: Brayton engine ca. 1876

Photo 6: Thomson, Sterne engine designed by Clerk

Photo 7: Clerk's 1881 engine

Photo 8: Clerk's 1877 patent

Photo 9: Clerk's 1877 patent

Photo 10: Clerk's U.S. patent of 1880

Photo 11: Clerk's home in Glasgow

Photo 12: Longitudinal cross section of Clerk engine

Photo 13: Clerk ignition valve

Photo 14: Tangye Robson engine

Photo 15: National engine ca. 1930

Photo 16: RMS Caronia

Photo 17: St. Peter and St. Paul Anglican Church

Photo 18: Clerk family's headstone

Photo 19: Sir Dugald Clerk in 1932