July-August 2018

The Two-Stroke Cycle

By Paul Harvey

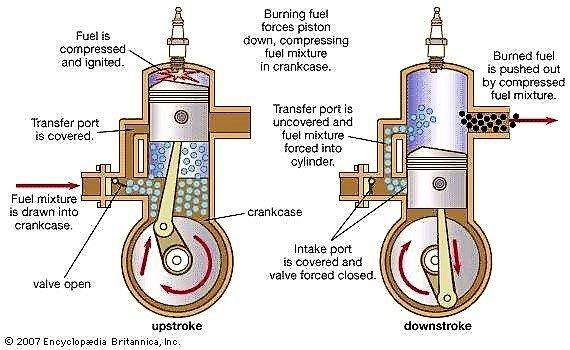

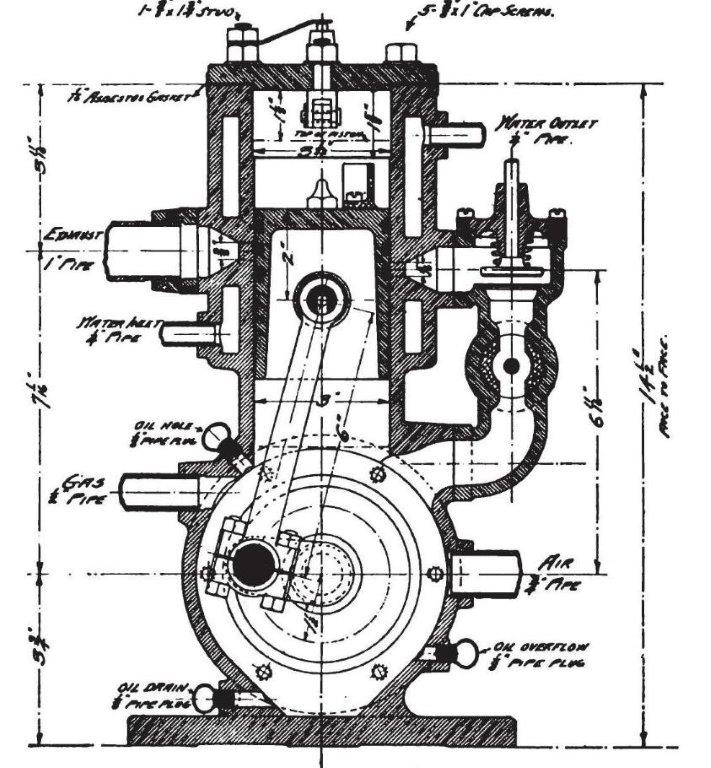

We all know what a two-cycle engine is, right? It's a little buzzy-sounding motor on your weed eater or chainsaw! They have been around as long as we remember, and we don't give them much other thought. Just mix some oil into the gas and they do the job. We just take for granted that they are called two-cycle. Actually, the term should be "two-stroke cycle", meaning that there are two strokes of the piston, one up and the other down, to complete a power cycle. The neat diagram in Photo 1 depicts that quite well. The two-cycle engine has power on every revolution of the crankshaft.

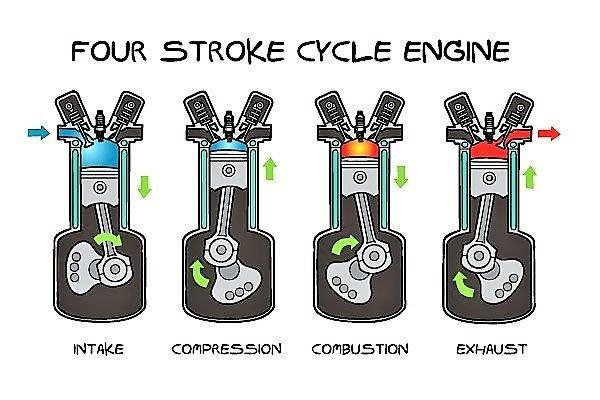

Then, one might ask, what is the four-cycle engine? These are the ones in our automobiles, farm tractors, and large equipment. Again, the correct term should be "four-stroke cycle", as there are four strokes of the piston to complete one power cycle. First, the piston goes down on the suction stroke, then goes up on the compression stroke, then down again on the power stroke, and finally up again on the exhaust. Another diagram, shown in Photo 2, illustrates this operation nicely. Note that the four-cycle engine has only one power stroke for every two revolutions of the crankshaft.

I intend to explore some of the varied history of the two-stroke cycle, who invented it, and how it came about, in this article. But now, let's turn back to the four-stroke cycle a bit as it was invented earlier than the two-stroke cycle engine. Imagine way, way back in time for a moment. OK, no engines then. Perhaps the first thought of building an engine to use explosive power (internal combustion) came from someone watching a cannon fire. Hmmm! Picture the barrel as the cylinder and the cannon ball as the piston. Presto!! You have an engine!! Neat concept; and so many tried with all kinds of cycles but few succeeded. Inefficient, noisy, and dangerous, said the public. The power to weight ratio was horrible. So what to do?

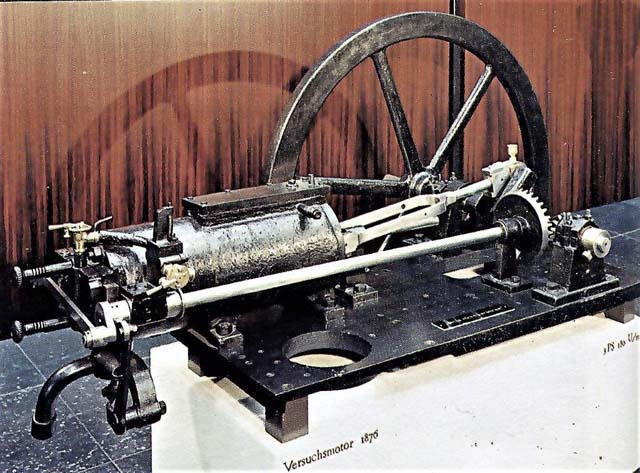

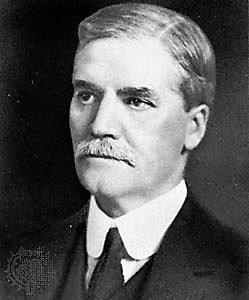

Then a German, Nikolaus August Otto, see portrait in Photo 3, gave it some deep thought. He understood thermodynamics and was aware of the Carnot Cycle, a perfect cycle of efficiency that can never be achieved. More yet, he had patience! And he learned from his mistakes. He reasoned that if he compressed the charge, he would get more power. Gosh, he was right!! In 1876, he was ready to market the world's first four-stroke cycle engine. Note Photo 4. It was a success and soon hundreds were being built in Germany, United Kingdom, and the United States.

But, as the saying goes, someone will try to build a better mousetrap; hence our tale of the Two-Stroke Cycle commences! As Germany fades behind, we cross the English Channel to Scotland and meet Dugald Clerk. His portrait is shown as Photo 5. Just two years after Otto's invention, Clerk modified a Brayton engine to produce power on every revolution of the crankshaft. Hello, two-cycle! We have a great new idea here, one that none had succeeded to do before.

Dugald Clerk was born in Glasgow, Scotland, on March 31, 1854, the son of Donald Clerk, a machinist. He studied engineering at Anderson College in Glasgow and Yorkshire College of Science in Leeds. A brilliant engineer, he also understood thermodynamics and could calculate engine pressures, temperatures, and power. During the First World War he was Director of Engineering Research for the Admiralty. For this, he was knighted as Sir Dugald. He built gas engines, wrote technical books and contributed much to the development of the two-stroke cycle. Many regard him as the father of that engine. He passed away on November 12, 1932, in Ewhurst, Surrey, England, but certainly left a legacy of knowledge and ideas behind.

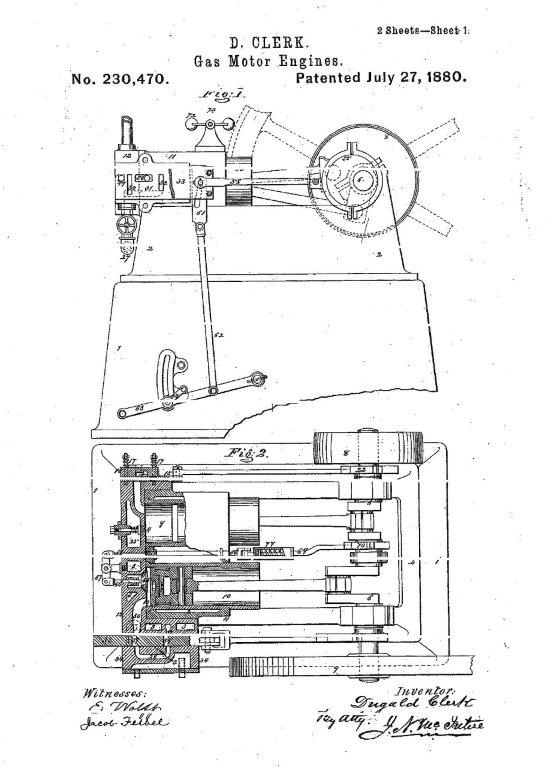

His aim was to build an engine that produced power on every downstroke of the piston and used compression to increase efficiency. He was indeed successful, but it required the use of a separate piston for charging the power cylinder, and he used valves. Four years after Otto's breakthrough, 1880, he secured an American patent for his machine. Please see Photo 6. Indeed, it was cumbersome using two slide valves and a poppet valve, as well as a second cylinder. But Sir Dugald proved his point and produced power on every revolution of the crankshaft. Best of all, the folks loved them as he produced his engines in the United Kingdom. Great job.

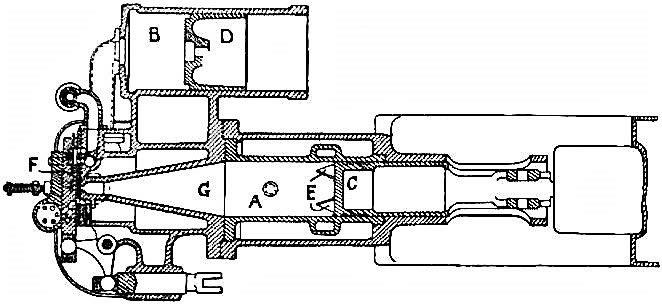

But Clerk was an untiring engineer and inventor and continued improving his engine. Note the sectional view of a later engine in Photo 7. This is a much more sophisticated machine with the power cycle operating the crankshaft and the pump cylinder attached to a pin in the flywheel. It still used a slide valve for ignition but now had an automatic poppet valve between the cylinders. Sound familiar, engine lovers? Yep, it is very similar to the Reid engine produced in Oil City, Pennsylvania. But enough of that now, as it will be the topic of my next The Flywheel article.

So we will leave Sir Dugald working on his engine in Scotland and cross Hadrian's Wall into England. Our imaginary journey will stop in the beautiful town of Bath where we will meet a very unique individual, Joseph Henry Day. See his portrait as Photo 8. He was born in London in 1855 and became a well-educated engineer attending the prestigious School of Engineering at the Crystal Palace. He moved to the town of Bath and established the Victoria Ironworks, famous for the cranes it produced. Here he became interested in gas engines and decided he could make a better one. I will defer from discussing his engine development for a bit, to continue with his somewhat eccentric life and demise.

Day remained a bachelor and lived in his father's house most of his life. He was brilliant in a way, but tended to get involved in too many projects. Having amassed a fortune with his Victoria Iron Works, he entered the mechanized bread-making business. Due to huge variations in the market, he lost it all. Cast into depression over this tragedy, he slowly realized that he was making another fortune from the license proceeds of his engines, especially those licensed in America. They made just dandy boat engines! Again on the top of the world, he entered into oil speculation in England. This venture was a folly and, despite his vigorous efforts, he again became penniless. He sank into oblivion in 1925, and it is thought that he died in 1946. No one is sure where or when. What a horrible fate for the gent who designed the engine that almost everyone uses today!

So, let's return to Bath and visit with Joe as he toils in his Victoria Iron Works. He tells us, "It seemed to me that all gas engines as then made were unnecessarily complicated and, therefore, expensive to produce, and that the only chance of cutting into the engine market was to devise something very much simpler." Indeed, he did just that!

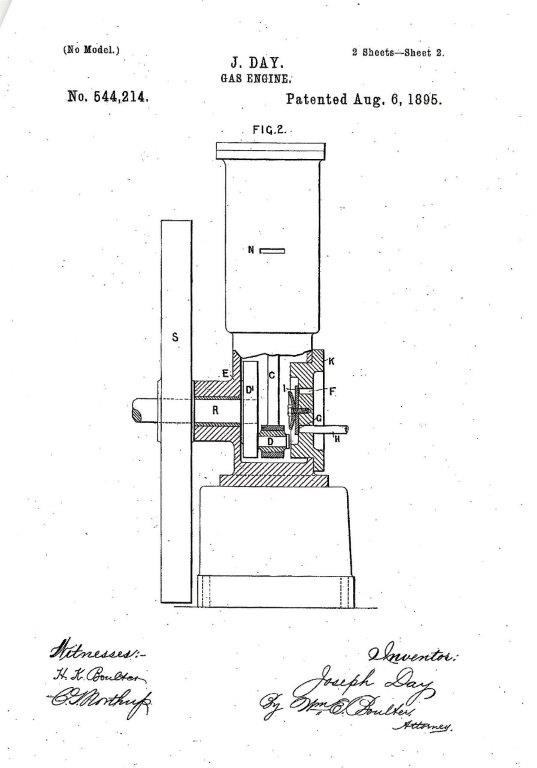

Day designed a two-port, two-stroke cycle engine that utilized just one automatic valve. The machine required an enclosed crankcase with a poppet valve on the side that was drawn open when the piston went up. As the piston went down, it uncovered openings, or "ports" in the cylinder wall that allowed the charge to be transferred from the crankcase to the power end of the cylinder. Wonderfully simple! He obtained a British patent for it on April 14, 1891, and an American patent on August 6, 1895. The American version is shown in Photo 9.

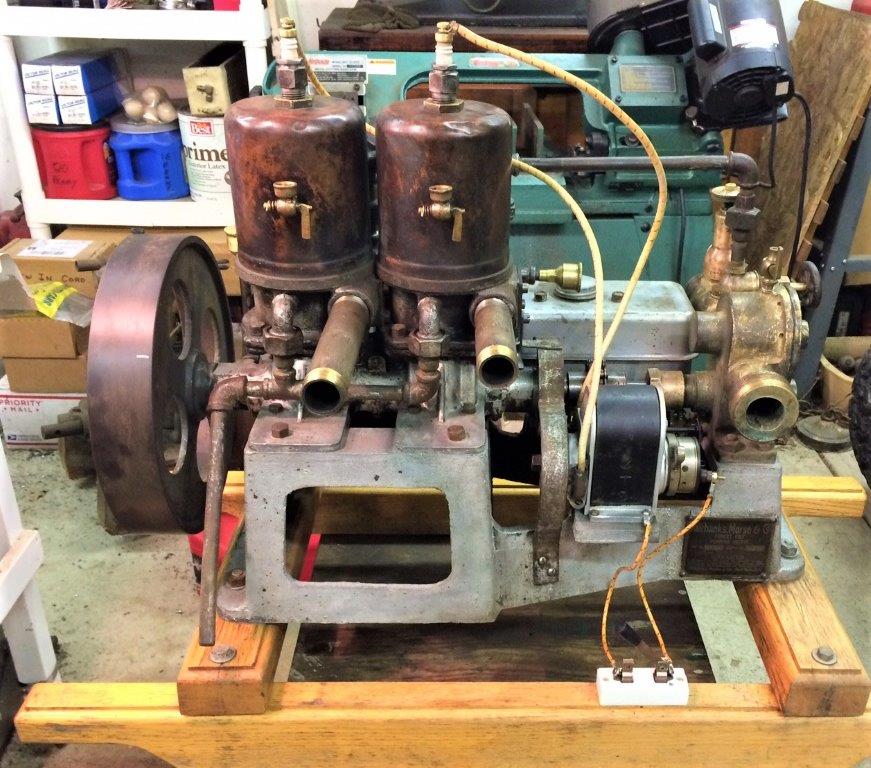

This marvelous design was light and versatile, and it produced power on every revolution of the crankshaft. One of the first American firms to license the engine was the Palmer Brothers Engine Company of Cos Cob, Connecticut. Note Photo 10. They quickly realized that with its excellent power-to-weight ratio, it would make a perfect engine for small boats. And indeed it did, and still does today. Many "two strokers" used in motocycles, go-carts, boats, and chainsaws still adhere to this identical design. If only Day knew!

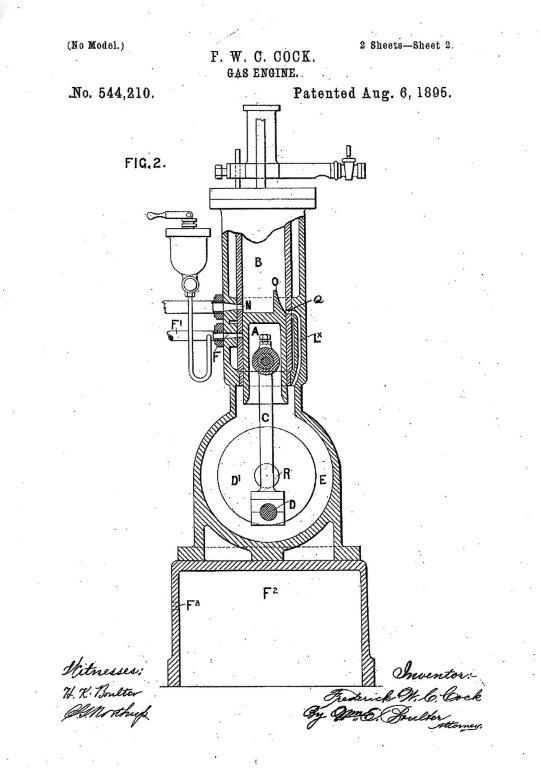

The Day two-port engine certainly revolutionized gas engine practice, but there is more to come. Imagine a complete and functional engine with just three moving parts. Impossible you say? Not so - just read on. About one and one half years after the Day two-port patent, one of his employees, Frederic William Caswell Cock (1863-1944), designed such an engine. Cock was granted an English patent for his design on October 15, 1892, and immediately assigned it to Day. The American patent was obtained in 1895 and can be seen as Photo 11. Simplicity personified!

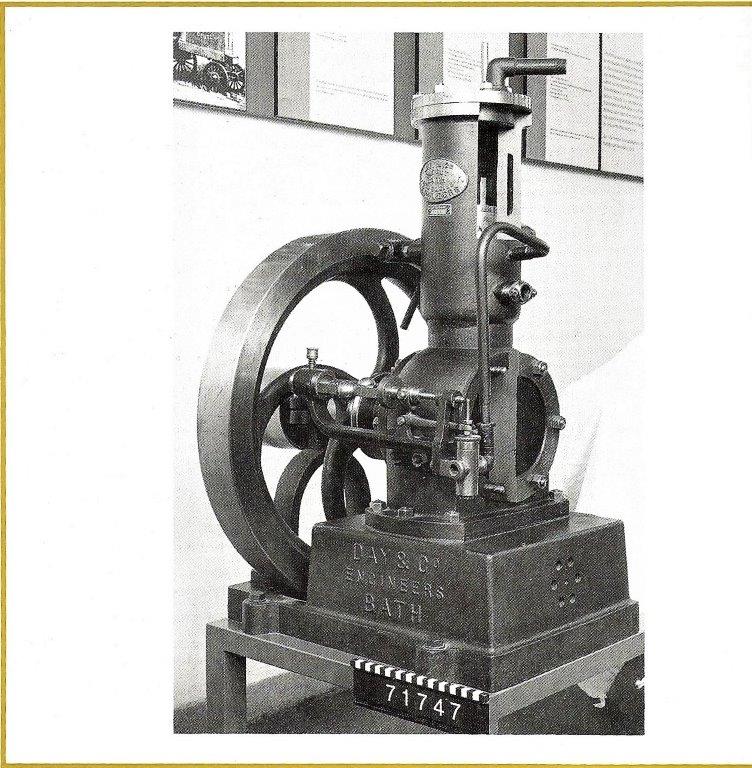

By studying the patent drawing a bit, one can see an engine with an enclosed crankcase and all the intake and exhaust functions controlled by the piston passing the three ports. Hmmm, it just makes one wonder why it was not invented earlier. Probably just too simple! Photo 12 shows a Day - Cock engine of 1892 displayed in the Deutsches Museum in Munich, Germany. These ingenious machines are still made today in all sizes and descriptions. And, of course, they have only three moving parts; the piston, the connecting rod, and the crankshaft. Success hinged on simplicity.

So, let's complete our journey by returning home to Coolspring Power Museum to see what might be lurking there. First we will look for some designs featuring two ports with a valve. Aha! Look at that little Bessemer in the Founder's Building. See Photo 13. It's two-port with a valve. Notice the exhaust comes out through the bottom of the cylinder by means of a port, and the valve is just to its right. Very successful, and Bessemer's successors are still building the two-stroke cycle in some very large machines. Wow! Next, we find this neat little National Transit vertical that is depicted in Photo 14. The valve is the device on the left side of the engine. We have many more, but these two will serve as fine examples.

So now as we stroll about, keep an eye open for some three port-engines. Look! Right in the Founder's Engine House near the Bessemer is the Mietz and Weiss two-cycle oil engine. By golly, it's a three-port without valves. Its image is Photo 15. Another fine example is this neat little Fairbanks-Morse fire pump that uses a twin cylinder Waterman three-port engine. It was designed to be as lightweight as possible so a couple of forest rangers could carry it to the fire, start it, and pump water. See Photo 16.

So this concludes my brief history of the two-stroke cycle engine. I have intentionally omitted details due to space constraints, but the reader who delves deeper will be richly rewarded. I do want to remind you the next time you browse through a Lowe's or Home Depot, just look at all those two-cycle engines on the various tools and tractors. Try to decide if they are two-port or three-port; it's fun! They just recall Joseph Day. Wonder if he ever guessed how many there would be and how long they are used. Before I close, I wish to remind the reader that in my next article, I will pursue the history and similarities of Dugald Clerk and Joseph Reid. Similar engines, different times, and different countries. Both born in Scotland. So join me by putting on a Sherlock Holmes cap and try to solve the mysteries. It will be great!

Photo 1: Schematic of two-stroke cycle engine (Encyclopaedia Britannica)

Photo 2: Schematic of four-stroke cycle engine

Photo 3: Nikolaus August Otto

Photo 4: Otto's four-stroke cycle engine

Photo 5: Dugald Clerk

Photo 6: Clerk's 1880 U.S. patent

Photo 7: Sectional view of later Clerk engine

Photo 8: Joseph Henry Day

Photo 9: Day's U.S. patent

Photo 10: Palmer Brothers engine

Photo 11: Cock's 1895 U.S. patent

Photo 12: Day-Cock engine of 1892

Photo 13: Bessemer "two-port with valve" engine

Photo 14: National Transit "two-port with valve" engine

Photo 15: Mietz and Weiss "three-port" engine

Photo 16: Fairbanks-Morse fire pump with Waterman "three-port" engine