March-April 2018

Scottish Glimpses

By Paul Harvey

Chapter One: James Howden

During the summer of 2017, Tom Rapp and I decided to return to Scotland for a train tour. My ancestors were from Scotland, so this tour really appealed to me. Of course, it offered to be an opportunity to gain firsthand information about some Scottish engine makers!

First on the list was Howden, since our flight took us to Glasgow where the old factory was located. Taking a taxi from the airport to our hotel, I asked the cab driver if she knew where it was. She did and, a short jaunt away, she stopped so I could get some photos. What luck! Coolspring Power Museum has a small Howden gas engine so exploring this firm sounded interesting.

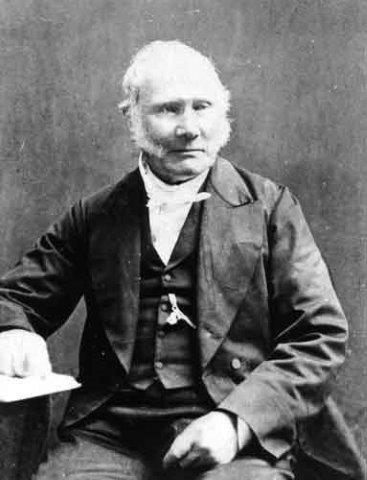

James H. Howden, Photo 1, was born on February 29, 1832, in the small fishing village of Prestonpans, East Lothian. His education was at the local parish school. Having had a long and successful engineering career and many patents, he passed away in Glasgow on November 21, 1913. He was best known for the invention of the Howden forced draft system which found uses around the world.

Howden settled in Glasgow where he did an apprenticeship in 1847. After several engineering jobs, he launched his own career in 1854. He invented a rivet making machine and sold the patent to a company in Birmingham. He was now secure financially and could devote his time to the design and manufacture of marine equipment. He considered himself a consultant engineer and designer and formed the James Howden & Co. to manufacture marine equipment.

His first big contract was to supply the Anchor Line ship Ailsa Craig with a compound steam engine and boilers. The engine was designed to run on 100 psi of steam, a pressure which was unheard of in 1857. He further experimented with preheated combustion air to gain efficiency. In 1863, he designed a very successful mechanical forced draft system for boilers and furnaces. It used a steam turbine to drive an axial flow fan. The heated air forced into the firebox provided substantial savings in the amount of coal used. The Lusitania, in 1907, used the Howden forced draft system. During World War I, the Admiralty ruled that, "all ships were to be fitted with Howden blowers so that they could outrun the U-boats."

Quickly outgrowing his original factory, Howden had architect Nisbet Sinclair design a new factory at 195 Scotland Street, in Glasgow. It opened in 1898 and featured overhead cranes, material handling equipment and central heating. It was expanded in 1904, then again in 1912. This factory was where the tunnel boring machines were made which were used to excavate the Channel Tunnel that connects the United Kingdom and Europe. Although Howden today is a global engineering business with branches on every continent, the original factory now lies vacant. Photo 2 and Photo 3 were taken by the author in August of 2017. The photos show many stages of development of this once magnificent red brick complex.

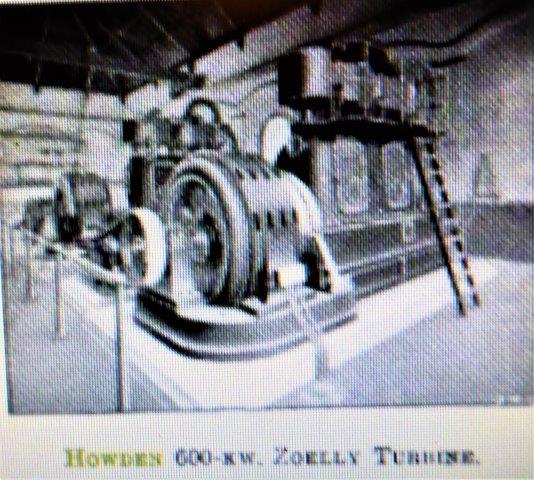

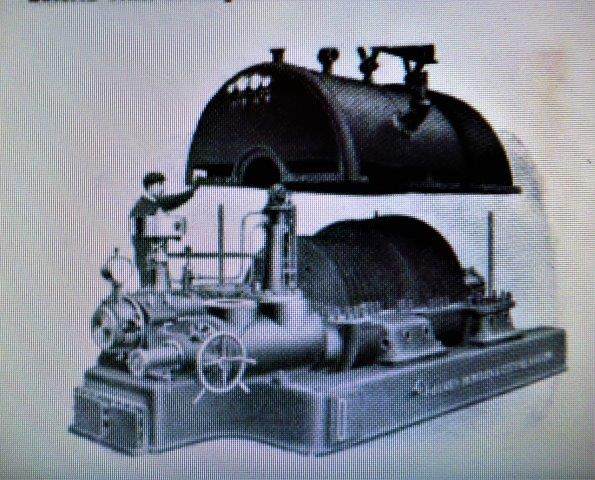

Howden developed a high speed marine steam engine that was later modified as the Howden-Zoelly engine and generator. Note Photo 4. His firm also developed and improved the steam turbine. Photo 5 shows an early one sporting a Jahns governor head. He built turbines into the many thousands of horsepower.

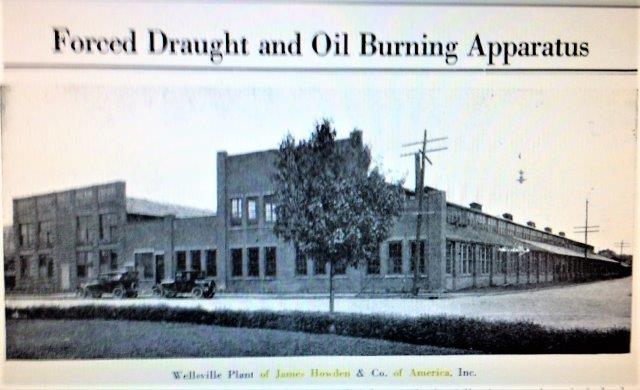

Although James Howden passed away in 1913, the company lived on and prospered. During World War I, the United States undertook a massive shipbuilding program. Seeing the opportunity, the James Howden Company proposed to the Emergency Fleet Corporation that they build a facility in America. In 1918, the James Howden Company purchased a suitable factory in Wellsville, New York. This branch was incorporated as James Howden & Company of America, Inc. See Photo 6. This facility had a large foundry, machine shops, and ample erecting space. It concentrated on building parts for the vital Howden System of Hot Air Forced Draught.

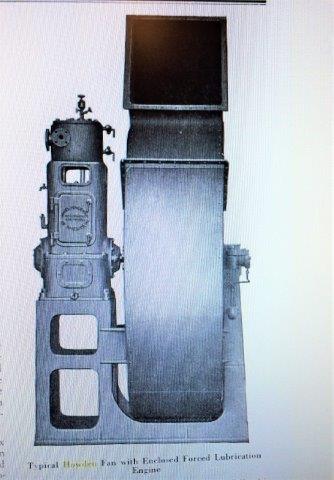

The Wellsville plant also built an advanced fan driven by a single-cylinder, double-acting steam engine with enclosed forced lubrication. Such a unit is shown in Photo 7.

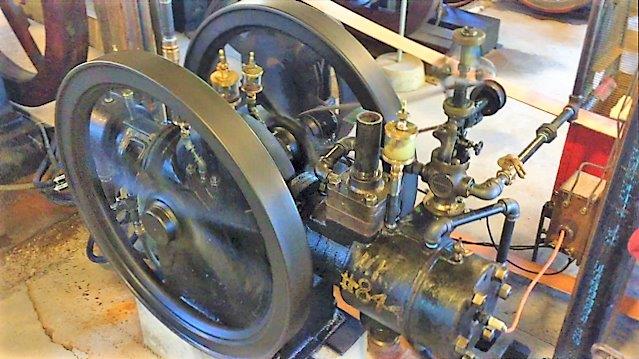

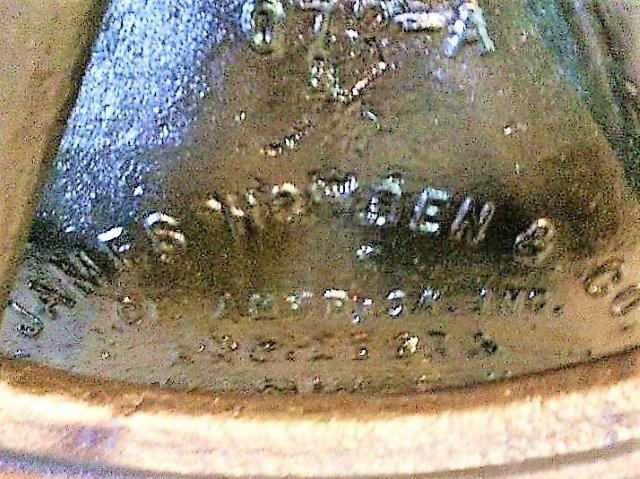

Earlier in this article, I mentioned that the museum has a small Howden gas engine. This engine is an amazing artifact considering that, in all the research I have done, I found no mention of gas engines. The museum's engine is a two-cycle gas engine directly attached to an opposed air compressor. These units were used to fill compressed air tanks which were used to start large gas engines, so they were meant for intermittent use only. It is seen running in Photo 8. Although there is no name plate, this detail of the frame, Photo 9, shows the name cast directly into it. Another mystery!

Our engine has the two opposed cylinders with the pistons of each connected by two rods. The compressor piston has the air intake valve in the piston head, and the discharge is through a poppet valve in the head. The compressor piston also serves as the crosshead, with the connecting rod attached there. The ignition is by spark plug powered by an Atwater Kent "unisparker." A special timer is attached to the crankshaft, which powers the matching coil. It is governed by a Pickering governor that is belt-driven from the crankshaft. As ungainly as it appears, the engine runs very well.

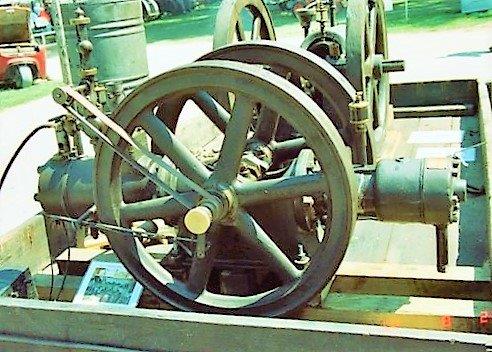

Clark and Norton, another firm located in Wellsville, New York, made an almost identical machine. One is depicted in Photo 10. There is no available information about this duplication. However, my opinion is that Clark and Norton made a few of these machines for Howden. It seems that the Howden shop was too busy with steam engines and forced draft fans to bother with small gas engines. On the other hand, Clark and Norton focused on gas engines and oil field equipment. They built very large engines and combination engine and compressors. Another mystery that makes this hobby so interesting!

Chapter Two: Reverend Robert Stirling

Just a few months before Tom and I had our adventure in Scotland, the museum featured hot air engines in its June Exposition. Preparing for the show, I discovered that the Rev. Dr. Robert Stirling invented the hot air engine at his home, Cloag Farm, in 1816. Rev. Stirling's portrait is seen in Photo 11. To my delight, I discovered that Claog Farm was about 35 miles away from Pitlochy, where we would spend the next two nights.

Our accommodation was the Killiecrankie House, as seen in Photo 12. Note the hill in the distance is topped with purple heather in full bloom. We were greeted at the door of this 1700s farm house by Bean, the cocker spaniel. He led us to Henrietta, the hostess, who got us registered. I explained my desire to find Cloag Farm and, amazingly, she said she would take care of it! When Tom and I returned later for dinner of roast guinea fowl, Henrietta explained she had arranged a "day hire" cab, and the driver knew the area well. It would be Sunday and first she would take us to her church with her.

An early breakfast the next day as our adventure was beginning. She took us to a small, rural church, then back to get our cab. The driver explained that Cloag Farm was near the village of Methven, Perthshire, and so we were off. Photo 13 shows the village with the farm circled in red. Note the beautiful rolling fields. Turning off onto a long gravel driveway, we were greeted by the sign seen in Photo 14. What would we find at the end of the road?

Entering a cluster of stone buildings, we met David Smythe, the owner. He was most gracious and gave us plenty of time to explore. He explained that there were only two buildings in 1816 when the engine was built, the back part of the house and the shop. Everything else was added later. The back part of the house, where Rev. Stirling was born in 1790, is seen in Photo 15. It was plain and simple, but also neat and cozy. The shop building was close by and is noted as Photo 16. What a feeling to stand on the ground 200+ years after Rev. Stirling did. On the way back, our driver took us to visit a water powered mill and Blair Castle. A great dinner just topped the day off!

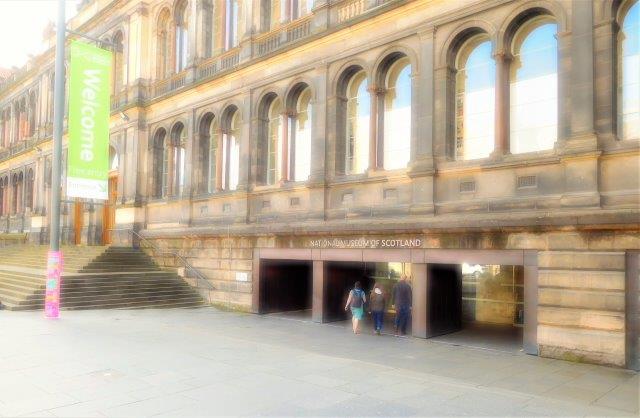

Now we wanted to see that first engine prototype that Stirling built at the farm. Back in Edinburgh, we walked to the National Museum of Scotland. See Photo 17. This magnificent structure, over one hundred years old, has great arched galleries filled with artifacts. We finally found the engine!!! As Photo 18 shows, it is a fantastic machine. A bit difficult to see due to the glass case, it stands nearly three feet tall. My desires have been fulfilled!

Next morning we were on an airplane heading home with so many fond memories to keep. It was a great trip!

The next issue of The Flywheel will be May-June 2018.

Photo 1: Portrait of James Howden

Photo 2: Howden factory in Glasgow

Photo 3: Howden factory in Glasgow

Photo 4: Howden-Zoelly engine and generator

Photo 5: Howden steam turbine

Photo 6: James Howden factory in Wellsville, New York

Photo 7: Howden steam engine-driven fan

Photo 8: Howden compressor engine

Photo 9: Detail of the compressor engine frame

Photo 10: Clark and Norton compressor engine

Photo 11: Portrait of Rev. Dr. Robert Stirling

Photo 12: Killiecrankie House

Photo 13: Methven, Perthshire, with Cloag Farm circled in red

Photo 14: Sign to Cloag Farm

Photo 15: The house where Rev. Stirling was born

Photo 16: Rev. Stirling's shop

Photo 17: The National Museum of Scotland

Photo 18: Prototype of the Stirling engine