September-October 2017

The Either

By Paul Harvey

Oil was discovered near Titusville, Pennsylvania, in 1859, and the world has been changed ever since. "Wildcatter" drillers risked their equipment and reputation to find new and richer oil deposits. A few were successful and found wealth with their discoveries. More importantly, they discovered that the oil deposits were located, more or less, in a line from Titusville extending into West Virginia. The northern fields were discovered a bit later. Washington County, located in southwestern Pennsylvania, proved to be an exceptionally big find. Production started in the late 1800s and continued long into the twentieth century. And so, the story unfolds.

Due to a naturally occurring inclination in the earth's crust, these new wells were much deeper than the ones near Titusville. This demanded that newer and heavier equipment had to be designed and manufactured. Initially, the wells were drilled with steam engines and large boilers. These units could drill the well, then stay on site to pump it. Eventually the large boilers aged and became unsafe as well as very costly to operate for a few hours each day as the production declined. There just had to be a better way!

At this time of need, Washington, Pennsylvania, had no manufacturers of engines or oil field equipment of any kind. Quickly, three new firms were born to help fulfill the demand. These were the Gardner and the Either of Washington and Tillinghast of nearby McDonald. Oddly, all three produced a combination gas and/or steam engine. Very few makers in other areas copied this unusual design, and very few of these engines escaped for usage in other areas.

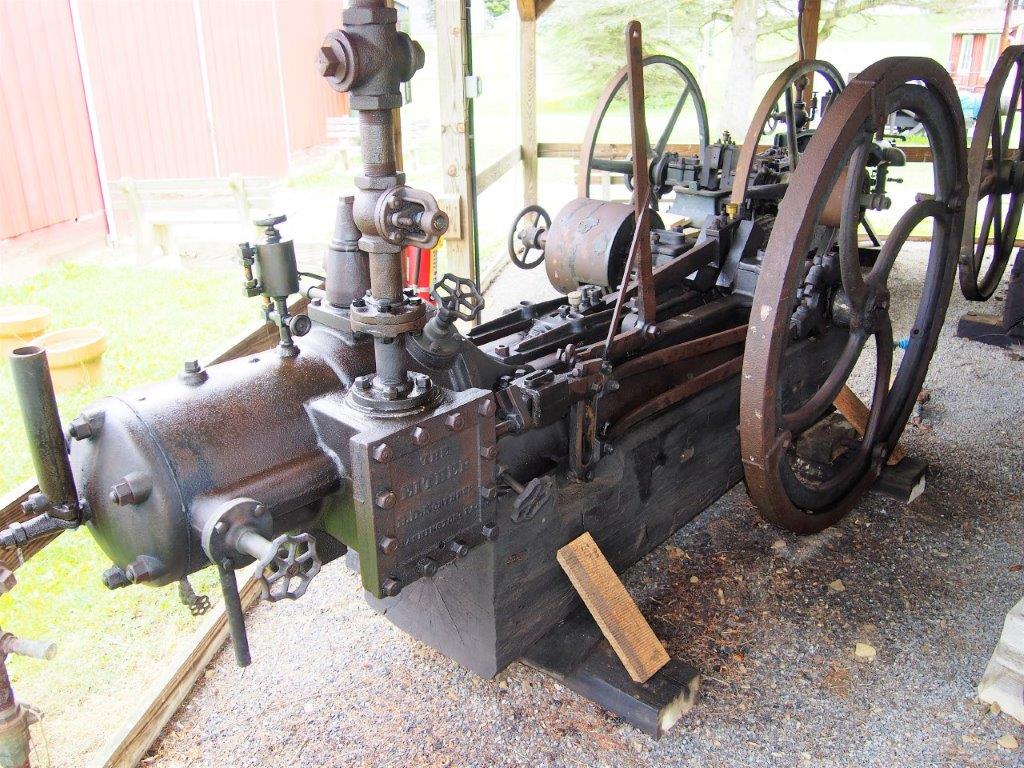

To help illustrate this discussion refer to Photo 1, which is the museum's Either engine. All three firms manufactured a cylinder that could be easily fitted to any flange mount steam engine frame. With the steam engine already on place, the cylinder manufacturer could utilize its frame, cross head, crankshaft, and flywheel. Of course, a clutch had to be developed and installed. With the new cylinder in place, the producer now had a gas engine to pump his well any time he wished. If he needed the steady power of steam to service the well, a safe portable boiler could be moved in to complete the process. This technology persisted into the 1970s. It was the best of two worlds!

The team of Dalhberg, Cliquenoi, and Uhlin had a pre-1900 patent assigned to Tillinghast, for a steam and/or gas engine. The cylinder was improved by several subsequent patents. This firm also produced an extensive line of compressor cylinders and related equipment. Gardner obtained his patent in 1904 and produced a wide variety of oil field equipment, as well as their gas or steam cylinder. The Either engine, built by B.D. Northrup was not patented; however, he started producing his design about 1907. These three engines would make a fascinating article, but, for this occasion, I will only discuss B.D. Northrup and his Either engine.

Blancher Dix Northrup was born in Pierrepont, New York, on November 27,1855. His father, Bushrod, was a machinist and his mother, Sarah, was a housewife. He slowly migrated south, obtaining various jobs in the manufacturing of oil field equipment, as well as gaining knowledge to build his own firm. In 1882, he married Emma Hollobaugh and they had three children: Mary, Burton, and Margaret. A business directory from 1897 lists Blancher and his family living in Washington, Pennsylvania, and he is noted as a machinist and founder. The Oil City Derrick of September 30, 1899, contains an advertisement that shows him as a machinist as well as an iron and brass founder. The ad promotes the Northrup Gas Regulator as the best in the field.

His business was very good, and in 1903 he built a large modern factory in Washington at the end of Third Street adjacent to the Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis Railroad. Unfortunately, both the factory and the railroad are long gone. However, he built his comfortable home about a block and a half away at 341 Jefferson Avenue. Photo 2 shows it as it appears today. He could easily have walked to work.

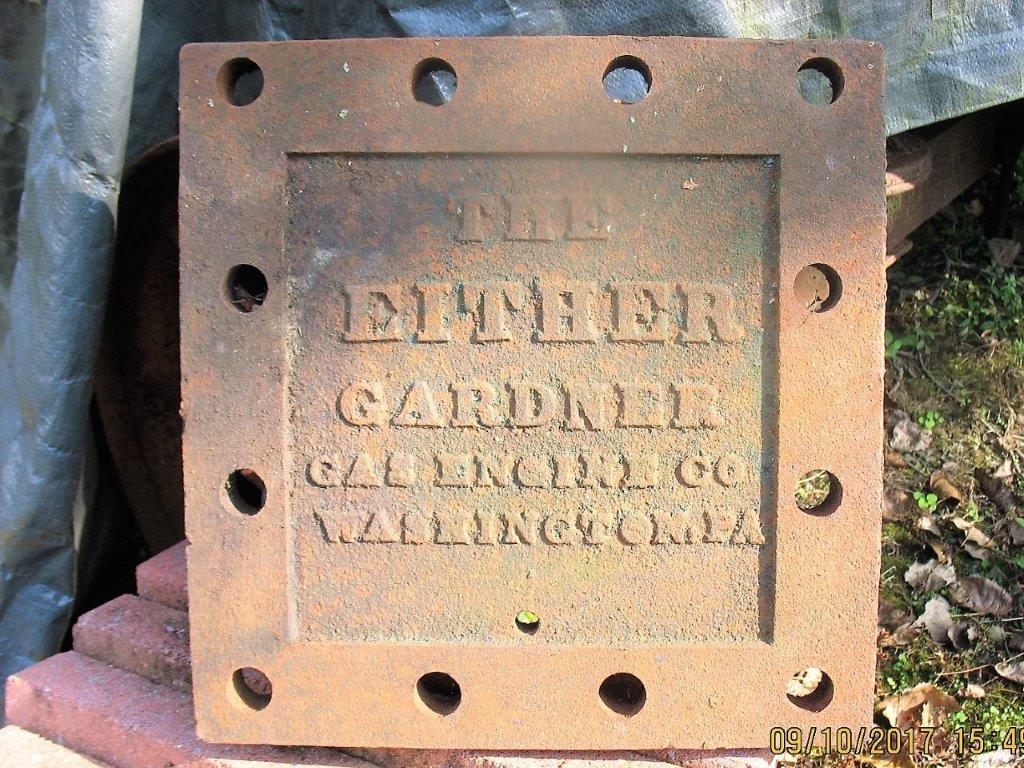

Apparently as his business flourished, he decided to design his own convertible gas or steam engine. He choose the name EITHER, which was very appropriate. This was 1907 when Gardner announced an improvement in their product, as well as placing their cylinder on their own very heavy frame. Competition must have been fierce, especially since Northrup did not have a patent for his engine. The Iron Age journal of August 17, 1911, announced that The Gardner Convertible Gas Engine Company was purchased by B.D. Northrup. Photo 3 shows an interesting valve chest cover that must date from the time of merger.

Northrup did design a clutch for the new line of engines. It is noted in US Patent number 975,987, of 1910. However, the buyer could specify the type of clutch he wished and it would be supplied.

A 1920 Washington city directory lists Northrup, then age 65, as machinist and factory owner. His son, Burton Earl, was working with him as machinist. Ten years later, Blancher is retired and his son is managing the business. He passed away quietly at his home on April 17, 1932, after a brief illness. He is buried at Washington Cemetery.

It appears that Burton Earl Northrup continued the business, and at sometime later the name was changed to the Washington Engine and Pump Company. Burton continued building various oil field equipment, but probably not the engines. One of his specialties was the Northrup "Go Devil" which was a pipe cleaning device that could be inserted into an oil line at one location and retrieved at another distant location. Traveling with the oil, it scraped all the goo out of the pipe. Burton retired in 1949 and sold the Go Devil, along with his entire company to National Transit. Burton passed away on June 26, 1950. This closes the Northrup story.

I did my Internship at Washington Hospital from July 1969 through June of 1970. After the years of school, it provided a relaxing time as well as a great learning experience - along with opportunities for collecting engines. In September, 1969, I purchased a 1946 Reo truck. After a brake job, a clutch, and a brush-on coat of Murphy's Super Tek enamel, I had an engine hauler! It proved dependable and I kept it busy during that year. It was particularly useful for an engine collecting adventure about 90 miles west of Washington. John Wilcox informed me of a 35 hp Hornsby-Akroyd (DeLaVergne) engine at Buckeye Pipe Line's York Station, located near Zanesville, Ohio. I was able to obtain the engine from York Station and take it home to Coolspring. Photo 4 shows the Reo in October 1969 as I was unloading the engine. My Dad can be seen looking on in amazement!

During my year in Washington, Pennsylvania, I was also able to enjoy many relaxing afternoons away from the hospital to explore the prolific oil field nearby. I soon learned that the Washington Oil Company had shops, offices and a yard in the nearby village of Taylorstown, Pennsylvania. Mr. Charles Jolly was the company president, and I am indebted to him for teaching me so much about the local field, as well as the operation of engines and oil production. He put the company together from a hodge-podge of leases, all using different pumping technologies.

Some parts of the field, including their small lease near Core, West Virginia, used JCs, Reids, and South Penns. These engines operated some of the deepest wells. Photo 5 depicts their pressure plant in Core. It used a Franklin Valveless gas engine direct connected to a compressor.

One area near Taylorstown had an empty brick building that once housed Westinghouse engines coupled to generators. Wells were pumped by utilizing direct current street car traction motors mounted on an iron frame of their own design. This arrangement made a compact machine that had a flat belt pulley to power the band wheel. The museum actually has one of these motor and pulley devices. The majority of the field was pumped by one of the three convertible cylinders already discussed. The Gardner was by far the most common, followed by the Either, and lastly, the DC&U. Note that these are my observations and not company records.

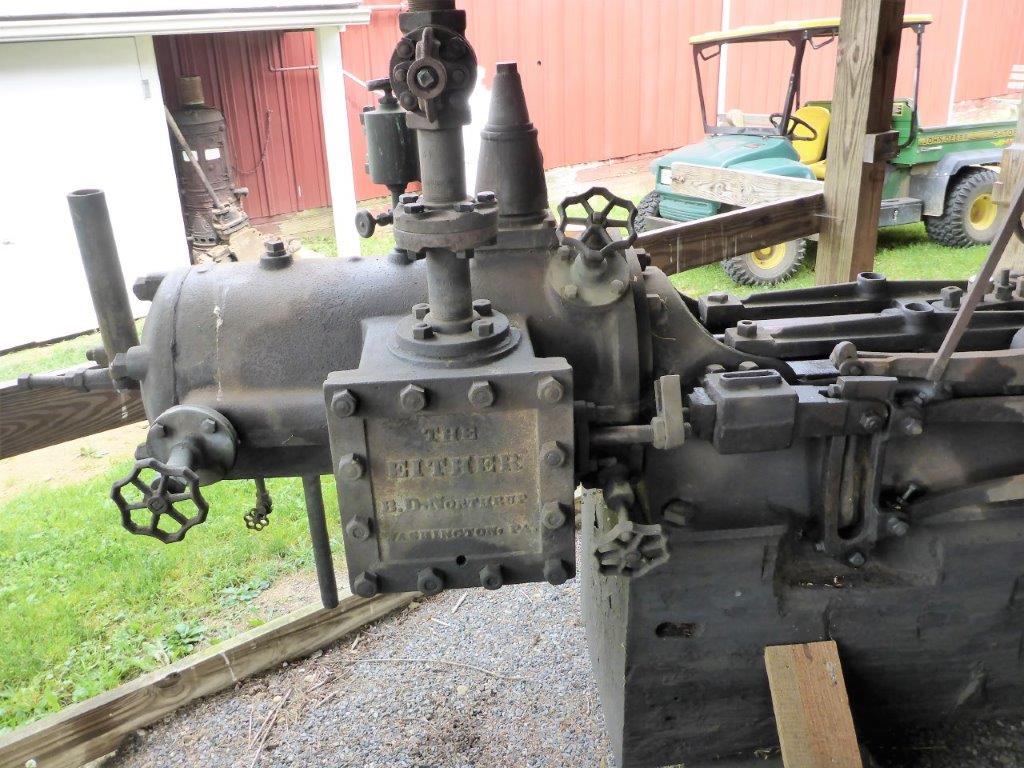

During that year, I was able to save two convertible engines: a Gardner and an Either. Both are housed in the Kougher Half Breed Pavilion at the museum. We will now discuss some of the details of the Either and its operation.

Photo 6 shows the pulley or "off" side of the engine. It appears much like a usual two-cycle converted engine from this view, as all the steam valve gear is on the other side. The large exhaust is actually the steam exhaust, and the gas engine exhaust is on the bottom of the cylinder. The valve on the top is the gas engine intake valve, and the hot tube can be seen on the head. The cylinder carries the number "86" while the frame has the number "2874". The frame, as well as the crankshaft, connecting rod, and flywheel are all from an Ajax steam engine.

Three interesting things are shown in Photo 7. Note the clutch and pulley, as it is typical of those Northrup built. It is operated by both a hand wheel and lever. However, most interesting is the square opening that had been crudely chiseled into the face of the clutch pulley. This practice was typical of all Washington Oil Company engines and was used to provide access for easy lubrication of the clutch bearing. Next, notice the typical "oil field" patch on the side of the frame to repair a crack. Machinery was repaired and not discarded in those days!! Lastly is the "balance" rim attached to the flywheel. Basically a steam engine practice, the engine would run smoother with the additional weight.

The valve chest and steam to gas controls are shown in Photo 8. The two inch pipe entering the top of the valve chest is the steam line. The valve would be a "D" valve operated by the Stephenson link and eccentrics of the steam engine. It can be connected quickly for steam use. Behind this on the cylinder is the "dunce cap"-shaped intake valve. It functions as a typical two-cycle engine intake. There are three similar valve handles on the side of the cylinder. For steam operation, the highest one is closed, which isolates the gas intake from the steam. Also, the other two, front and rear, permit the steam to enter the cylinder. Two engines in one!

I certainly hope the reader has enjoyed this article about such an unusual engine. My next issue of The Flywheel will be January-February 2018.

Photo 1: The museum's Either engine

Photo 2: Blancher Dix Northrup's former home in Washington, Pennsylvania

Photo 3: Either valve chest cover

Photo 4: Hornsby-Akroyd engine being unloaded in Coolspring

Photo 5: Pressure plant in Core, West Virginia

Photo 6: "Off" side of the museum's Either engine

Photo 7: The clutch and pulley of the Either engine

Photo 8: Valve chest and steam/gas controls of the Either