October 2016

London's Engines

By Paul Harvey

This past August, Tom Rapp and I returned to

However, our motivation was to visit three preserved steam sites: the

Photo 1 shows the magnificent

The huge suspension beams arching up to each tower are actually riveted wrought iron. Photo 2 shows a huge and highly decorated link in this design. The bridge is crossed by 40,000 pedestrians and 20,000 vehicles a day, as well as making about three openings a day for ships to pass.

The old engine room is open to the public, and Photo 3 shows one of the beautifully restored steam engines. One of the two was slowly rotating on compressed air, and was a delight to see. The engines were tandem, cross-compound, and operated a hydraulic pump in front of each high pressure cylinder. Photo 4 shows one of the high pressure hydraulic pumps. Deemed the most advanced and largest hydraulic system of its time, the pumps delivered river water to one of two huge accumulators, as noted in Photo 5.

The accumulators then delivered high pressure water to hydraulic engines in the base of each tower. These three-cylinder hydraulic engines, one set up on display, opened the bascules through a set of massive gears that finally meshed with a gear sector on the bascule. Photo 6 shows the display hydraulic, or water-powered, engine, which included a huge hydraulic brake and clutch. Opening time for the bridge was 90 seconds! The original engine house and boiler stack is shown in Photo 7. A day can be easily spent there, and it is a "must see" for any engine enthusiast.

Our next adventure was at the Science Museum, as noted

in Photo 8. Although the museum does not operate its

engines, viewing the massive display is an enjoyable way to spend a

day. Upon entering, one finds a great hall containing two rows of

ancient beam engines. Photo 9 illustrates the 1838 beam

engine of Boulton and Watt. Note that the engine already has a high and

low pressure cylinder - quite advanced for the time. The steam age had

reached

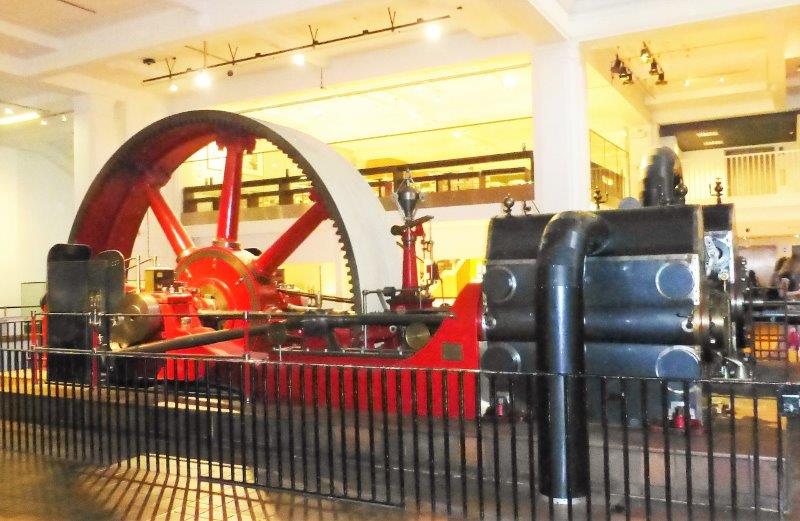

Photo 12 shows a Maudslay engine built in 1840. Henry Maudslay was a meticulous engineer and trained many of his employees to become competent steam engineers. The latest engine in the great hall was this Burnley Iron Works cross-compound steam engine of 1903, as shown in Photo 13. It worked until 1970. Note all the rope drive grooves in the flywheel. It would be great to continue, but there were just too many more exhibits to be able to describe them in this article.

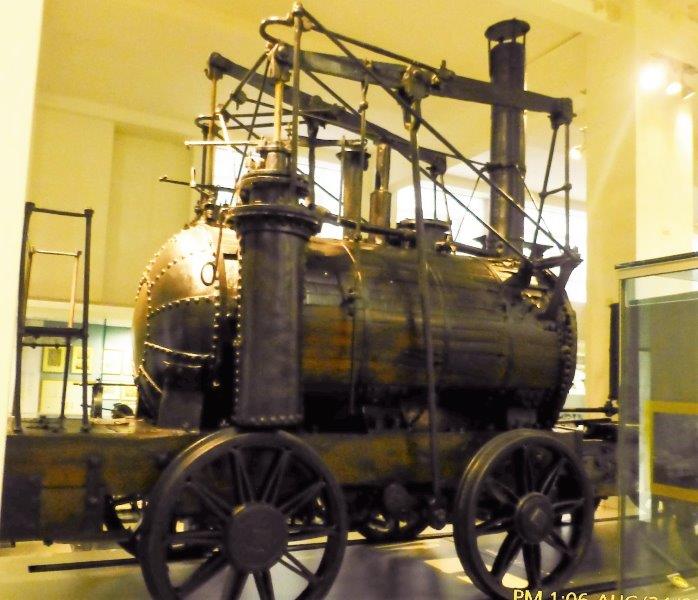

The next room contained a huge display of railroad

engines, trucks, engines, and machine tools. Photo 14 is

the oldest steam locomotive in the world. "Puffing Billy" was built in

1814 and transported coal to the canal five miles away. It was finally

retired in 1862. Among all the steam engines, I found this 1865 Lenoir

gas engine so beautifully intact. See Photo 15.

Across the room was this 1931 Fodon Diesel Lorry, "lorry" being the

English term for truck. It was one of the first Diesel-operated trucks

in

Photo 17 shows a model machine shop built between 1850 and 1880; little information is available about its history. It is fascinating with all the diminutive tools working and operated by line shafts powered by tiny leather belts. It is now operated by an electric motor and watching it provided a great end to a perfect day.

Our last - and best - tour was at the London Museum of

Water and Steam, formerly the

We first went to the "original" building which is seen just behind the standpipe. Containing the two largest beam engines in the world that are still in their original location, they are impressive beyond imagination. There are stairways going to the second and top level, over three stories up! Originally used by the engineers for lubricating and servicing the engines, they are now open to the visitors. The 90-inch engine was installed in 1840 and the 100-inch in 1869. These measurements are the diameters of the steam cylinders! Interestingly, the engines do not have flywheels.

Photo 20 shows a portion of the top of the 90-inch engine, and Photo 21 illustrates Tom standing by its beam. The steam enters the top of the massive cylinder under low pressure and forces that piston down, which raises the pump cylinder and weight chamber. The pumping is actually done when the steam condenses, forming a vacuum bringing its piston back up. This is helped by the weight of the pump plunger and its 50-ton weight chamber. The stroke of the pump is eleven feet, and the engine operates at four cycles per minutes, pumping six million gallons per day.

Photo 22 shows the engineer starting the

90-inch engine. He does an intricate "dance" operating three long

levers, gradually increasing the engine's movement. Finally, when

it reaches full stroke, he latches the levers out and it continues to

cycle itself so quietly and gracefully. In Photo 23,

one sees the pump plunger and the 50-ton weight box on top. It

actually pumps water in recirculation. Photo 24

shows me sitting by the beam of the 100-inch engine - note the name on

the beam! This engine was obsolete in 1869 when installed, but the

water authority wanted a matching engine. Both were retired in

1944 when the Allen diesel

These two engines are called "Cornish" beam engines.

Interestingly, the people from

Photo 25 shows a 20-foot waterwheel, powering a three-cylinder water pump. Placed in service in 1902, it pumped water for the Duke of Somerset's estate as well as for the nearby village's drinking fountain. Continuing to view the outside exhibits, we found this 1862 Trench fire pump operating under steam; see Photo 26. The water works acquired it from the city in 1876, and its main use was pumping water from burst water mains. It was impressive to hear it working hard under the load of a high pressure hose.

The Allen Diesels were installed in 1934 to help with

the increasing demand for water in

In the new exhibition building are more operating steam

engines. The Dancer's End is seen in Photo 28. This twin

beam engine does seem to dance when in operation, Built in 1867, it got

its name from pumping water for Lord Rothschild's estate at Dancer's

End. Photo 29 illustrates the

No visit to

Next month we will take a tour of the Coolspring Power Museum's new pavilion and all the engines that have been installed. It is a great display, but we also have exciting plans for its further expansion.

Photo 1: The Tower Bridge in London

Photo 2: Bridge Link

Photo 3: Tower Bridge steam engine

Photo 4: High pressure hydraulic pump

Photo 5: Hydraulic accumulator

Photo 6: Hydraulic engine

Photo 7: Engine house and boiler stack

Photo 8: The Science Museum

Photo 9: 1838 beam engine of Boulton and Watt

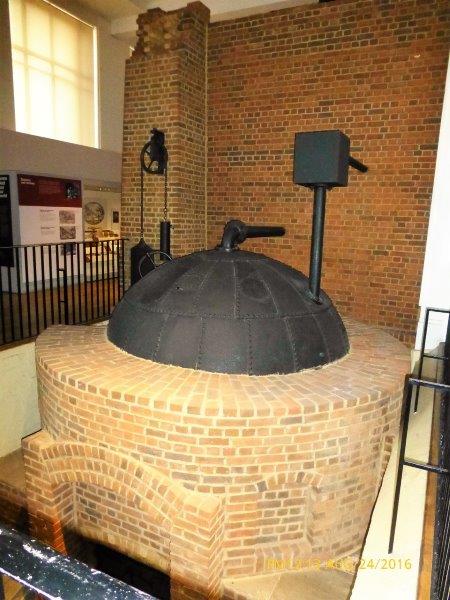

Photo 10: Newcomen engine

Photo 11: 1796 Boiler for the Newcomen engine

Photo 12: Maudslay engine

Photo 13: Burnley Iron Works engine

Photo 14: Puffing Billy locomotive

Photo 15: Lenoir gas engine

Photo 16: Fodon Diesel Lorry

Photo 17: Model machine shop

Photo 18: London Museum of Water and Steam,

formerly the

Photo 19: Model of the station

Photo 20: Top of the 90-inch engine

Photo 21: Tom and the beam of the 90-inch engine

Photo 22: Engineer starting the 90-inch engine

Photo 23: Pump plunger and 50-ton weight box

Photo 24: Paul and the beam of the 100-inch engine

Photo 25: Waterwheel-powered pump

Photo 26: 1862 Trench fire pump

Photo 27: Allen Diesel engine

Photo 28: Dancer's End engine

Photo 29: Easton and Amos engine

Photo 30: The triple engine

Photo 31: Elizabeth Tower which houses Big Ben