|

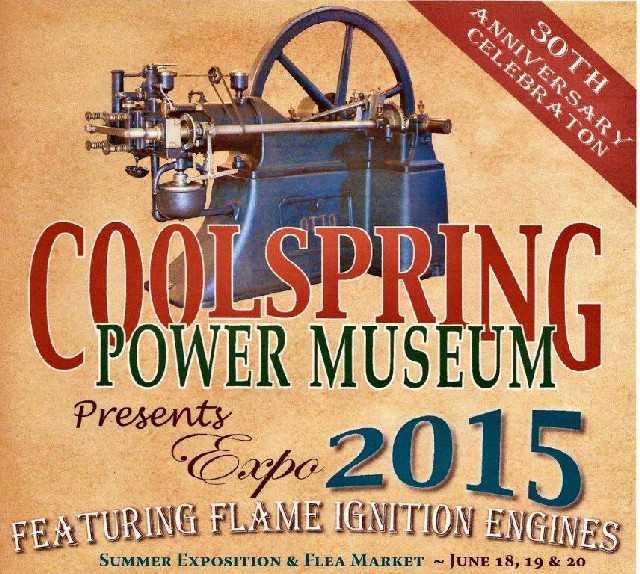

June 2015

Flame Ignition Engines

By Paul Harvey

As the summer solstice approaches,

Coolspring Power

Museum is preparing for its magnificent

Thirtieth Anniversary Celebration, the Flame Ignition Expo. This

promises to be our largest event ever! As an unprecedented gathering of

the rarest flame ignition and centennial engines from across

North America, it will be the largest and most significant

event of its kind ever shown. The dates are June 18, 19, and 20,

2015. Indeed, it will be a much larger version of our Centennial Engine

Expo of 1995.

The museum has worked diligently for the past year to

make this great show possible. Monumentally, a new, climate controlled

structure has been erected, thanks to our generous donors. Joined to

the Susong

Building, it will double its size and

initially be used to house some of our exhibitors' most prized

possessions. Designed by our late Curator of Collections, Preston Foster, it will be

dedicated to his memory during the show as The Preston Foster Hall.

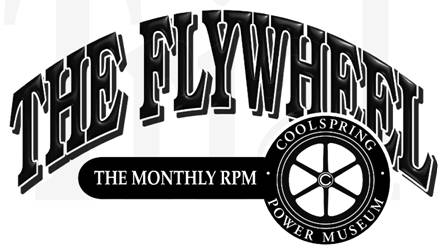

Photo 1 shows Preston, his faithful

Husky, Kanu, and one of his beloved Foos engines. He is sadly missed by

the museum, his friends, and the entire gas engine world.

We expect about forty flame ignition engines from all over the United

States and

Canada to arrive for display and operation at the event.

These will range from machines weighing several tons to toy engines.

All will have been built before 1900, and many in the 1870s and

1880s. They will be displayed in three prime locations to give the

visitor easy access, as most will be operating.

By now, the reader is probably wondering what a flame

ignition engine is? The answer is quite simple! It is an engine that

has a device to introduce an open flame into the cylinder to ignite the

fuel charge, creating the explosion that makes the power. Usually,

this is accomplished by a moving slide valve that is loaded with a tiny

bit of gas at one location, ignited as the slide moves, and at the

precise moment, transferred to the cylinder. Boom! The cylinder

explosion occurs and the flywheel turns. Just think of the Revolutionary

War soldier touching a flame to the breech hole in a cannon to cause it

to fire. In so many different configurations of the same principal, the

early builders usually chose this method of ignition, long before the

spark plug was designed. Our modern engines still repeat the same

cycle, but cause the ignition with a spark plug. The ensuing explosion

produces the power which is transferred to the piston.

One must keep in mind that these early inventors,

mostly from Europe, had nothing to copy.

Perhaps thinking of that cannon, they had the dream of igniting a

combustible fuel inside a cylinder to produce usable power. Their

inventions soon challenged the steam engine and its troublesome boiler, and they helped introduce the industrial revolution. Many variations

were tried; some were successes and others were failures. To simplify, two

classifications developed, compressing and non-compressing. The

non-compressing engines simply drew in a fuel charge, ignited it, and

the further expansion developed the power. Although some were

successful, they were very inefficient and were gone by 1900. The

compressing engines are the ones we know today. They draw in a fuel

charge on the intake stroke, compress it, then fire it. This is more

efficient and produces more power. I will show some examples of both

classes, and these can be viewed in operation during the Expo.

Non-Compressing

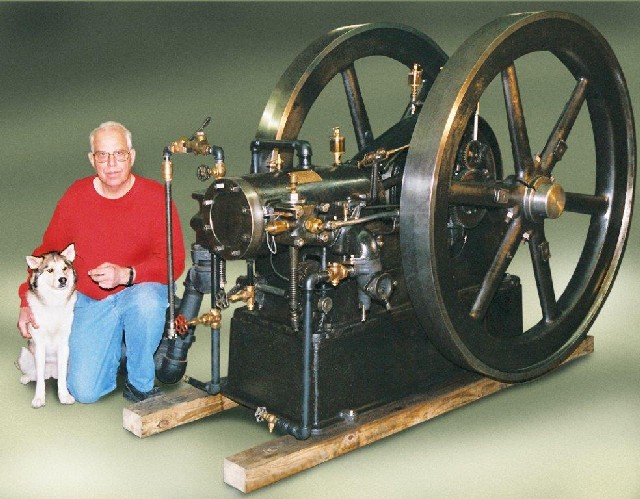

The first example, Photo 2, is the

magnificent 1867 Otto Langen engine made in

Germany. This is the oldest operating

gas engine in the Americas,

and will be displayed here for the Expo on a special loan from the

Rough & Tumble Engineers Historical Association of Kinzers,

Pennsylvania. It does not have a crankshaft,

but uses a rack and pinion device to transfer the power from the piston

to the flywheel. These were actually quite successful and several

hundred were built. It is one of the forerunners of all subsequent gas

engines.

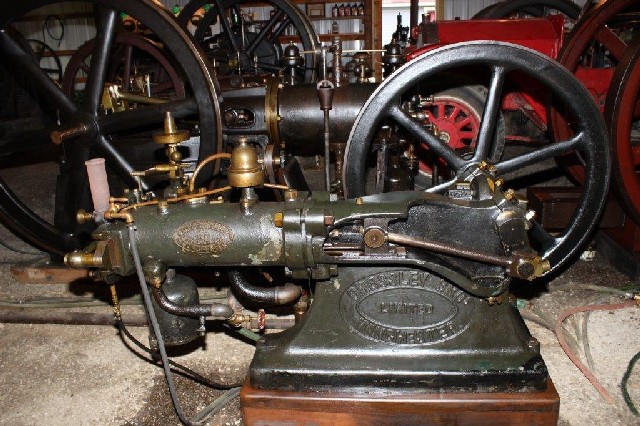

Photo 3 displays our Sombart gas engine.

This is a non-compressing two-cycle engine that proved successful for a few

years. This engine does have a crankshaft and provided a reasonable

alternative for a steam engine in small shops. Ours is rated at five

manpower! Yes, manpower, and not horsepower.

My last example is the little Crown pumping engine shown

in Photo 4. Designed by Lewis Hallock Nash and built by

the National Meter Company of New York City,

these small engines were integral with a water pump. Popular in the

1880s, they could pump water to the top floors of the high buildings

were it was stored in a cistern for use. They were simple in design and

very easy to use. We expect to have about eight displayed.

Compressing

The museum's oldest operating engine is this

Schleicher-Schumm built in Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania, in 1882. The centerpiece of the

Susong Building,

it is shown in Photo 5. This engine develops two

horsepower and originally operated a print shop in

Dover, Delaware. It uses

a slide mechanism in the head to transfer the open flame to the

cylinder, following the German Otto design.

Photo 6 displays this beautiful 1888

Schleicher-Schumm engine. Note that it now carries the Otto Gas Engine

Company name. It powered a small machine shop in upstate

New York, and was abandoned for many years. Now

restored to its original glory, it will be displayed at our Expo, and

probably stay on long term loan. Still using the open flame, slide

valve ignition, it shows several improvements from the above engine.

Many of the makers preferred to use the inverted design

for their smaller engines. Seen in Photo 7 is an inverted

Crossley engine made in Manchester,

England, in 1890. Crossley obtained

the German Otto license very early to make their own slide valve

engines The inverted design had more problems than advantages and was

essentially gone by 1905.

This 1/2 horsepower Crossley, vintage 1889, has been on

loan to the museum for many years. It is slide valve, open flame

ignition and runs superbly, producing one half horsepower. It would

have been ideal to power a small lathe, a printing press, or a large

sewing machine. Note the side crankshaft on this small engine. It is

shown in Photo 8.

Toys

The kids of the 1880s and 1890s loved their "hi tech"

toys every bit as much as our kids like their electronic gadgets. Even

with the limited media coverage of the past, the new gas engine was

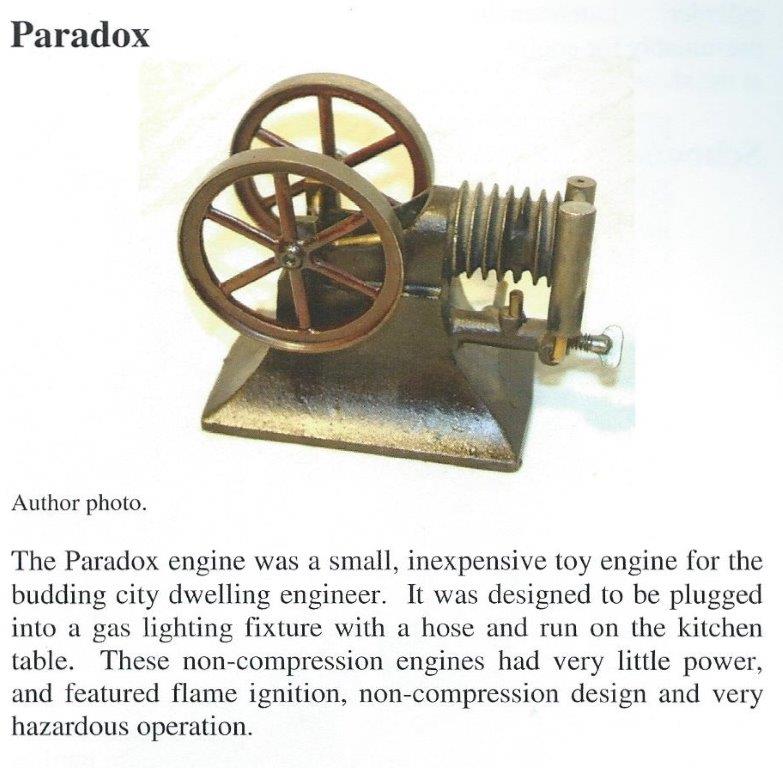

certainly in the forefront. The little Paradox, shown in Photo 9,

was a cast iron toy engine that could fit in ones hand. It

boasted the open flame ignition, non-compressing principle. It could

run hours and hours, to the delight of the kids - the future engineers

of gas engine development.

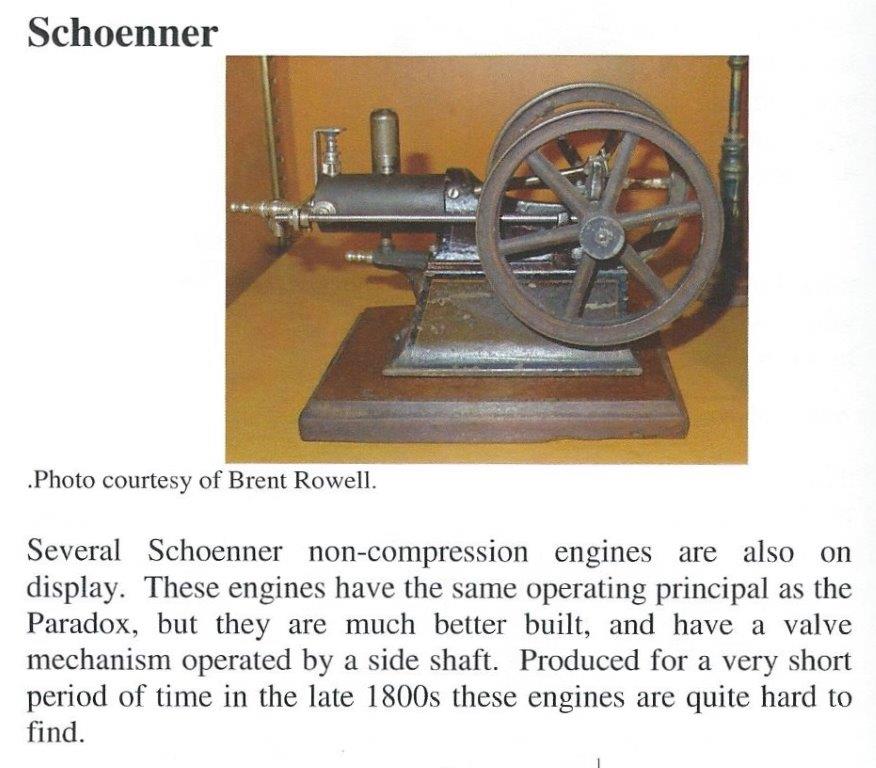

The Schoenner, seen in Photo 10, was a bit

bigger and better built toy engine that used the non-compressing

design. Produced about 1890, it actually used a rotating side shaft to

operate the valve. They were open flame ignition and made enough power

to operate another small toy. Note the wood base shown in the photo.

Books

Two very special publications have been prepared by our

capable show co-chairmen; Woody Sins and Wayne Grenning. Woody has

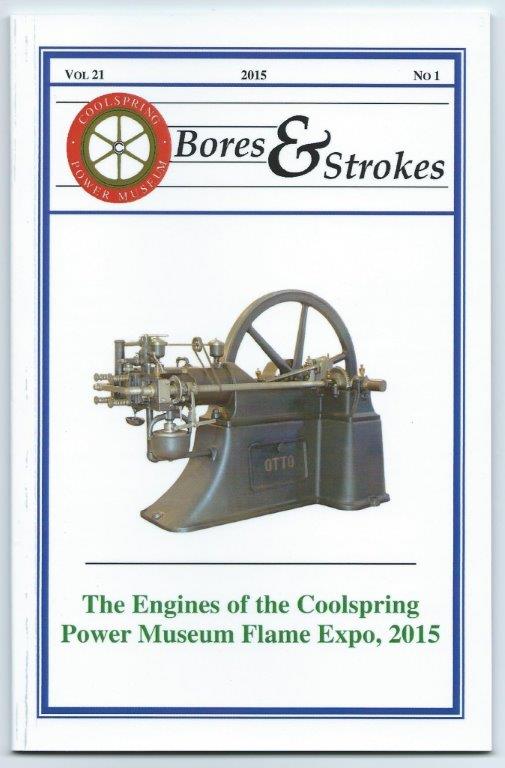

written our yearly booklet, Bores & Stokes. Titled The

Engines of the Coolspring

Power

Museum Flame Expo, 2015, it

actually is a "field guide" of the museum's engines as well as many of

the ones our exhibitors will display. See Photo 11. This

44-page work starts with a detailed explanation of the flame ignition

designs, copiously illustrated for easy understanding. Photos and

descriptions of the engines follow, each with photo and most in color.

Buy this book at the museum's gift shop when you arrive for $4.50 and carry it

with you as you tour the flame ignition engines. Then take several more

home for your friends!

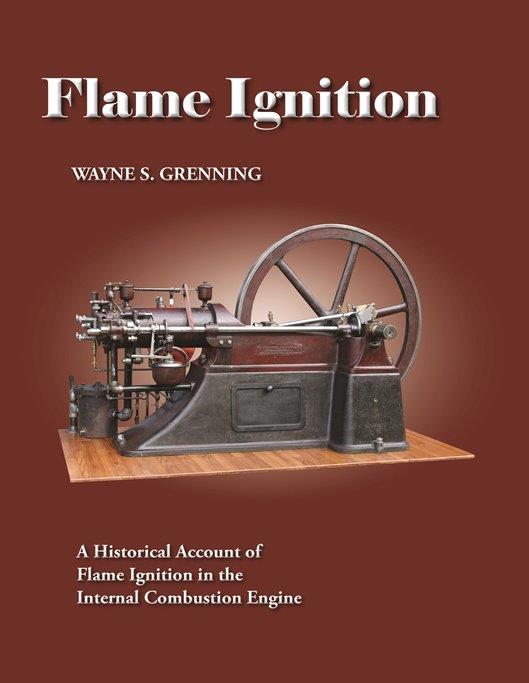

Wayne has

researched flame ignition extensively for many years, and his endeavors

have produced an 875-page hardbound book titled, "Flame Ignition."

Most of the information has never before been published. Note the

cover shown in Photo 12. To quote, this is "A Historical

Account of Flame Ignition in the Internal Combustion Engine." The work details all the

early designers and dreamers from the very beginning. It has several

hundred illustrations and photos with more than half in color. This is

a book to enjoy today, refer to again and again, and then take a prime

location in your engine library. Published by

Coolspring Power

Museum, the printing will be limited to

1,000 copies. Available at the gift shop, the regular hardbound

version will cost $79.95. There will be 100 copies, consecutively

numbered and signed by the author, done in deluxe goatskin leather

binding for $149.95 each. The museum is proud to offer this work.

Coolspring

Power Museum's

grand Thirtieth Anniversary Show is almost here, Photo 13.

I hope you will be able to join the celebration and enjoy all the

flame ignition engines. For more information, please call 814-849-6883

or see our website at coolspringpowermuseum.org. You will enjoy! Next

month, The Flywheel will continue with Part 2 of "The Genius of Verona."

See you then!

|