|

October 2012

When a Diesel Isn't a Diesel

By

Paul Harvey

With the year rapidly ending and the October Show just around the

corner, the museum is already thinking of 2013 and our next season.

Our featured group of engines for next year will be "Oil

Engines." So what is an oil

engine? I guess one first thinks

of the diesels powering so many modern vehicles and equipment and that

is partially correct. An oil

engine is one that burns a liquid fuel that is sprayed into the cylinder

and ignited by the heat of compression and not an electric spark as in a

gas engine. It is true that

gasoline engines use liquid fuel and fuel injection spray, but it is

ignited by the spark and not the heat of compression.

This makes a big difference in design and economy.

At the turn of the last century, there was a myriad of designs of oil

engines and probably the most noted was the Diesel.

Dr. Rudolph Diesel, of

Germany,

invented a compression ignition engine about 1894 that was remarkably

efficient but very complicated in design.

He did not have the technology or materials to make the high

pressure injection systems of today's engines so he chose to use high

pressure air at about 1,000 psi to essentially blast the fuel into the

cylinder. He had found that he

needed about 500 psi of compression to heat the air enough to cause

combustion. This required a

direct connected multi stage air compressor and a very heavy and rigid

frame to support the inherent stresses.

These engines were used in marine and stationary applications and

the practice ended in the 1920s.

It should be noted that oil engines are frequently all grouped together

and are termed "diesels." When

this is done, although not correct, diesel is not capitalized.

The actual engines that follow Dr. Diesel's design are correctly

capitalized as "Diesels."

Actually preceding Diesel's design by two years was Herbert

Akroyd-Stuart of

England.

He invented a lower pressure compression ignition engine that was very

successful. It has been discussed

in an earlier issue of The Flywheel.

By eliminating the need for the high pressure air and all the

necessary equipment to produce it, he contributed much to what we now

know as diesels.

Another line of oil engines was the two-cycle, moderate compression, hot

bulb start ones based on the design of Carl Weiss and built by Augustus

Mietz of

New York City.

These required heating a bulb or similar device in the head for initial

start and then it would run on compression ignition.

This is very similar to the glow plugs in some of our engines of

today. Many makers soon followed

the initial Mietz and Weiss design in producing very successful

machines.

However, the topic of this writing, is the high compression engines that

used a spray cup to inject the oil.

This small cup received its charge of oil, metered by a needle

valve controlled by the governor on the intake stroke of the engine so

it was essentially gravity fed.

During the compression stroke, the cylinder temperature, as well as that

in the cup rose finally causing ignition of the oil in the cup.

This small explosion then sprayed and vaporized the oil out

through four small holes into the cylinder and then the secondary or

power explosion occurred in the main cylinder.

A very ingenious and efficient way to produce a low cost and yet

efficient oil engine.

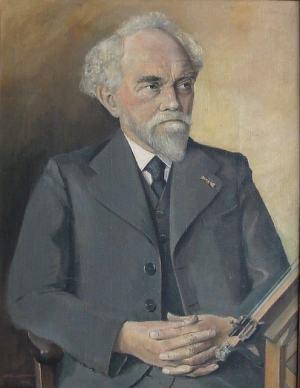

This design was invented by Jan Brons (1865-1954)

of the

Netherlands.

See portrait in

Photo 1.

Jan initially became a carpenter but had a knack for mechanical

things and began experimenting with oil engines at an early age.

He was attracted to the Diesel engine and set about to make an

engine that would operate without the troublesome air compressor.

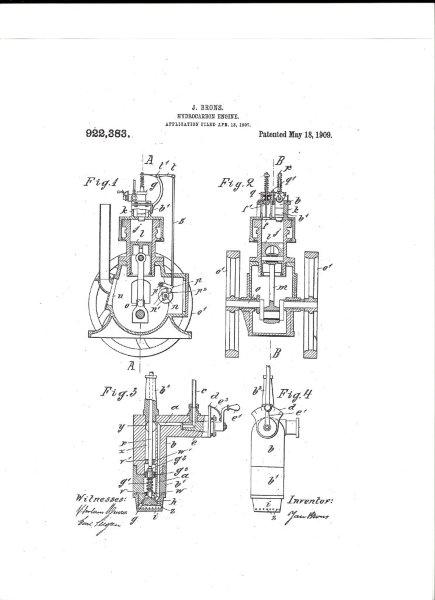

He was successful and awarded a patent in 1904.

See

Photo 2.

His engine operated well and soon he had a factory at

Appingedam,

Netherlands

producing them. The spray cup

pre-chamber was very simple as shown in

Photo 3 and made him

successful. By 1920, 95% of his

production was exported.

Production

of the Brons engine continued until 1946.

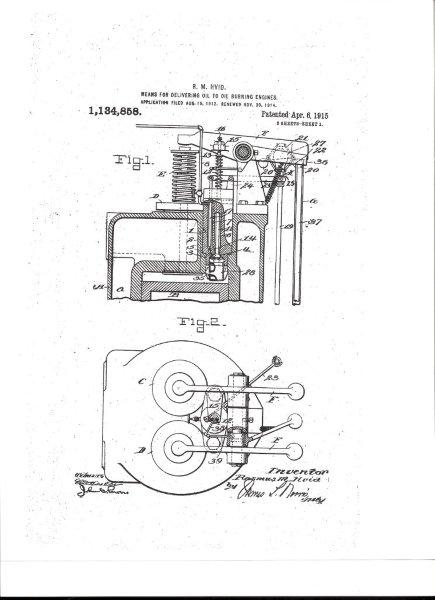

Finally the Brons design was introduced into

America. Rasmus Martin Hvid

(1883-1950)(pronounced "veed") was born in

Denmark

and became a naturalized

US

citizen. Being mechanically inclined, he studied the Brons engine and

made some changes to the spray cup. He applied for a

U.S.

patent in 1912 and was granted in 1915.

See Photo 4. Establishing

the R.M. Hvid Co. on

July 12, 1912,

in

Battle Creek,

Michigan,

he decided not to produce engines but to sell his patent license to

other firms for production. This proved very lucrative for him selling

a license for $2,500.00 and receiving a royalty of $5.00 for each engine

produced. By 1916, he had sold eleven licenses and the number was fast

increasing. It is interesting to note the his improvements in the spray

cup proved troublesome and he soon bought a license from Brons to

produce his design. This was a good move as it prevented any patent

infringements and continued Hvid's success.

One of the first licenses went to St. Marys Machine of

St. Marys,

Ohio,

and later of

St. Charles,

Missouri.

Under the direction of chief engineer, Haus. L. Knudsen, they developed

a line of very large and successful Hvid injection engines.

To current knowledge, these were the largest Hvids built in

America.

Photo 5 shows the four horsepower St. Marys at Coolspring Power Museum.

It originally powered an air compressor to start larger engines

at a Buckeye Pipe Line Co. station.

Another early licensee was the Hercules

Engine Company of Evansville,

Illinois. We are not sure whether St. Marys or

Hercules obtained the first license. Obtaining their license in 1915,

Hercules was already a major manufacturer of engines. Their line

consisted of horizontal hopper cooled farm engines of smaller horsepower

rating. They already had an excellent market with Sears and Roebuck

selling their engines under the Sears name of Economy. Hercules new

Hvid injection oil engine was termed the Thermoil and was made on their

gas engine frame using the higher compression Hvid principle. This

proved to be a disaster for both Hercules and Sears as the gas engine

frame just would not withstand the oil engine stresses and broken frames

were common. So many were returned that it proved to be a great

financial loss. We witnessed this same problem with the early adaption

of a gas engine to a diesel by General Motors. However, they did not

give up and returned with the redesigned Model U Thermoil. Initially

built in 6 hp and 8 hp, and later improved into 7 hp and 9 hp, these

engines were literally indestructible! They were successful but almost

impossible to start in cold weather. But when running, they proved to

be very powerful and economical being able to use many of cheaper heavy

oils.

In 1919, Clessie Cummins was tired of being a chauffeur and became

interested in oil engines. He was a rural farm boy with no formal

education but was especially interested in engines. He formed the

Cummins Engine Company in

Columbus,

Indiana

and obtained a license to build the Hvid engine. His engines were

similar to the Thermoil and were also sold by Sears. They were very

successful but Sears offered a money back guarantee so a farmer would

get one, use it for the season, then return it with some complaint.

Sears returned a great portion of these engines to him which nearly

caused bankruptcy. His former employer, Mr. Irwin, financed him and

went on the develop the Cummins diesel that we all know today. That

story is very interesting and well documented elsewhere.

Photo 6

shows the museum's 9 hp Model U Thermoil.

I acquired this engine in 1967 from the Eureka Pipe Line Company

of

West Virginia.

It was belted to a small National Transit triplex pump at their Eddy

Station which was located near Core, WV.

This was a tiny station that pumped crude oil from several wells

over the mountain to the larger Dolls Run station in Core.

The story goes that the engine one time wrapped up the belt which

flipped it off the foundation landing upside down.

It was merely reset and good as new!

Also told were stories of cold weather starting where the

engineers built a fire outside to boil a five gallon can of water to

pour into the hopper to heat the engine.

Then one got on the crank and the other pulled the belt to get it

running. It runs well here during

the summer months. I hauled this

engine home on my Dad's 1952 Ford F1 pickup truck and I think that was

the most it ever carried. This

was one of my early adventures to move an engine and it all came out so

well.

Photo 7 shows the museum's

7 hp Model U Thermoil.

Our final Hvid injection engine at Coolspring Power Museum is this 9 hp

Parmaco.

Photo 8.

It is essentially a Thermoil with many additions.

Note the side shaft and the vertical governor head.

Parmaco stands for Parkersburg (WV) Machine Company and a few

were built for pipe line use. Two

are noted to have survived. They

all were very cantankerous to start but quite dependable when running.

This one came from Star Station of the Buckeye Pipe Line Company

in

Ohio.

It is now set up in its own building driving the original horizontal

Parmaco pump. It moved crude oil

from a local lease to a larger station where the oil went on to the

refinery.

It is my hope that the reader has enjoyed this little venture into the

realm of an oil engine that is not a Diesel.

To see many more in operation, please attend our June 2013 show.

Now, our big Fall Show, Swap Meet, and Flea Market is fast

approaching. We will have many

exhibitors, a swap meet, and a good flea market.

Of course, many of the museum engines will be running with a

special night run on Friday evening starting at

7 pm.

There will be plenty of tasty food as well as our famous home made ice

cream with the New Hollands turning the freezers. It is October 18, 19,

and 20 so please try to attend.

For more information, please call 814-849-6883.

The museum will be closed for the winter after our October event,

but special showings and tours can be arranged.

Please call at least one week in advance to arrange.

See you then!

|